To clarify the new discipline plan which accompanies the Community Pledge, we met with Restorative Practices Committee members Director of Equity and Inclusion Jenn Wells, Dean of Social and Emotional Learning of Upper School Nicole Beck, Director of Middle School Sean Fitts, Interim Director of Upper School Jawaan Wallace and History and Social Sciences Department Head Mabel Wong.

UV: What is restorative justice?

Beck: Restorative practices have been used in indigenous communities for centuries around the world and that is just the way of life in those communities. Pivot to countries around the world using restorative practices in their Judicial Systems, restorative practices in education borrows from that Judicial System practice. Within a school system, restorative practices seek to move away from punitive forms of discipline which when conduct has happened or the rules are broken, punishment is put on a student. Restorative practices move to who is harmed and what is the root of the behavior. Historically, restorative justice in education was used in a lot of public school systems to move away from the high rates of suspension and instead look more at why students who continually get to the suspension phase of behavior are acting out in this way. Marlborough is not a school with a high rate of suspension and we are not necessarily concerned with the same conduct that public schools that started implementing restorative practices early on are. So we will use the language restorative community and restorative practices.

UV: What sparked restorative practices at Marlborough now? Was there a particular event?

Fitts: We’ve spent some time in the last two years looking at discipline, especially through an equity lens and looking at what decisions we made and our process for making decisions. It goes back to the idea: why do we have to make someone feel bad for a mistake they made? Is that an effective system to help them right the wrong and also have a positive impact on the community? We also went through the process of looking at our honor code. The principle of the honor code is great and made sense, but was the system supporting those principles and were we getting to the place where we wanted to be? It was pretty obvious that it just creates more negativity when we hand out punishments as the solution to a problem instead of having a conversation and building relationships and trying to figure out why the student was having behavioral issues. I think our lived experiences in the school shows that punitive consequences don’t change the system, and over the last few years both student feedback and our lived experiences have shown us that there is something problematic. What kind of systems and structures exist that penalize an individual? For example a student commits a micro aggression related to race and we penalize the student, but that doesn’t get to: why does the student do it, what structures have we cultivated that have allowed the student to do it or made it seem like it was okay?

UV: We understood that consequences after an event are dealt with more on a case by case basis. How do you prevent bias from emerging in such an individualized process?

Beck: I just want to say there’s still a code of conduct. There’s still a student handbook. There’s still conduct policies and behavioral policies alongside the restorative practices that we’re using. So I think that’s a common misconception, not just in Marlborough, but in a lot of spaces as they’re moving and shifting, from punitive to restorative, that it’s just this kind of free for all. Like you’re going to sit around in a circle and talk about everything and it’s all kumbaya. And we know that that’s just not reality. And so the logical consequences are still there when harm is caused, depending on the severity of it.

Wells: I think what’s happening is there’s a misunderstanding that we’ve replaced the code of conduct or rules at the school with restorative practices. That would be inaccurate, it’s more that we are starting a paradigm shift at the school. So the paradigm shift is more from a punitive approach to our community, to more of a restorative approach throughout the community.

UV: What does a peace circle look like? How does a victim stay protected when in those conversations?

Beck: A person who harm was caused against would never be forced to be in a circle if they didn’t feel comfortable being in that. It really is largely dependent on the person who harm is caused against. And if they say I don’t ever want to see that person face to face, we would never make that happen. It’s a long process and it’s complex in that it takes more thoughtful consideration. With a conduct infraction, I don’t have to look at you or talk to you. I can just enter it in the computer and then maybe we never talk about it again, versus there are maybe seven or eight steps that need to occur here involving many different people. So we’re not referring to it as a policy change because it’s not. It’s a process and it’s a way in which we’re doing things.

UV: If a student is harmed by a teacher in the classroom, how do you expedite the resolution process for a student who needs to be in that class still but has also still experienced harm?

Beck: I think it would depend on the level of harm. If you were the student and you did not feel safe being in that classroom, we would make accommodations for finding an alternative class. Or if needed, teacher removal would happen while there is an investigation going on.

Fitts: In the past, typically there would still be a conversation with the teacher if something happened, but it would be a memo write up that would get into a file and that would be the end of it until something else happens. There may be a recommendation for some kind of professional development if things are continuing, but it’s a very closed, confidential process. And this is a more open conversation that involves many people. It does take more time. Of course, we’re going to address the needs of the student right away. We’re not going to place them back in the classroom unless we’d resolved the situation ahead of time. With this, we’re building the community more and we’re not just disciplining the teacher and then putting the information in a file and burying it.

Wallace: And I think what’s confusing from the outside looking in is that many of these things are extremely confidential. And so you may not know or see any of these things, but they absolutely are.

UV: What experiences do committee members bring to the table?

Beck: I was introduced to restorative practices in 2005 when I lived in the country of Fiji for a few years and informally introduced because that’s the way of life there. When I worked in Chicago public schools, that’s where I had formal training in restorative practices within a school community.

Wong: And I’ll just add that as a classroom teacher who teaches subject content that deals with topics that could be contentious and sensitive, my entry into this was because I was teaching that class and I was like, what am I going to do given the broader political landscape of the moment that continues today as well. So I started implementing some of these practices and I found that they do make a big difference.

UV: I think a lot of people understand when there’s a serious offense, like plagiarism, people have a good grasp of the consequences of that. How are smaller offences dealt with in a way that incentivizes change in behavior?

Wallace: I’d say for instances like trash on the field and things like that, a very similar process would take place. I think what students don’t probably know is that we do track that information. If it’s something that’s repeated, obviously we’re going to take action towards correcting that behavior. But I would say that we’re hoping to make expectations clear and also talk about the impact. Who is affected when you leave trash on the field, what does that impact have on our facilities staff or to our costs?

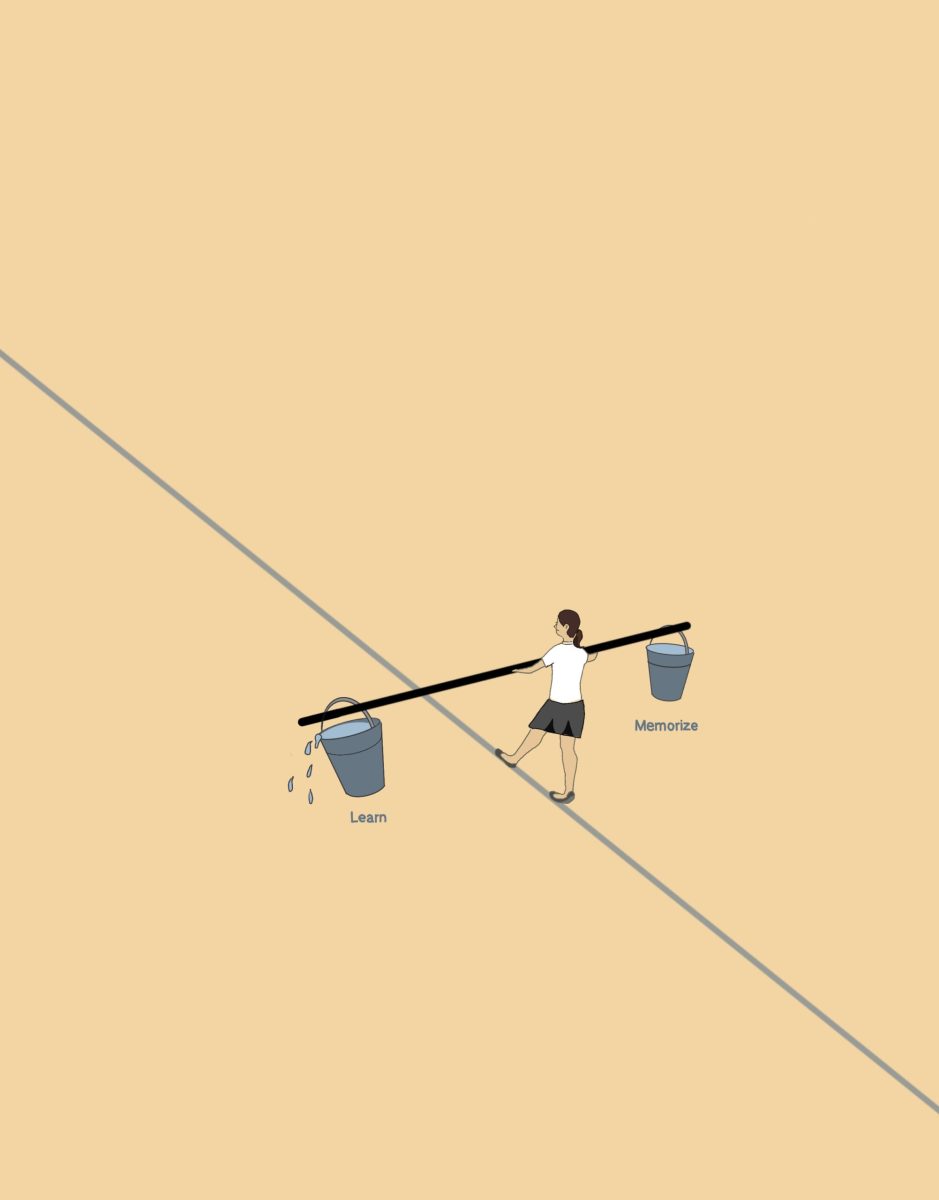

Beck: What’s tricky is that we’re all swimming in the water of a punitive system because that’s all we’ve known our entire lives. So unlearning that and learning something new is clunky. And that’s where we are in this process right now.

More information about restorative practices at Marlborough will be included in the Restorative Practices Student Handbook, which is currently being drafted.