By Christina ’16, Katharine ’15, Car ’17

Entering Marlborough as a freshman in 1973, Mel Veal Preimesberger ’76 was among the first African American girls to attend Marlborough. After informing one of her teachers at her public middle school that she wanted to attend an all-girls school, Preimesberger’s teacher informed her that both Westlake School for Girls—now co-ed Harvard-Westlake – and Marlborough were both looking to promote diversity in their communities. Upon visiting Marlborough’s campus, Preimesberger said that she fell in love with the School. Reflecting back on her time as a cheerleader and newspaper reporter during high school, Preimesberger fondly recalled her experience at Marlborough in a community that she said welcomed her and supported her.

“I think that everything that the School was doing and all that it had to offer at that time was bigger than [racism],” Preimesberger said.

Just over 40 years later, the demographic of the Marlborough student body has evolved dramatically. Today, students of color make up 38% of the student body. The School makes efforts to promote diversity through All-School Meetings, diversity clubs and the Face It Retreat, celebrating different cultures and bringing attention to issues arising from diversity.

How did the integration of the School happen? Why is it that we as a community never talk about the School’s integration? What is the School currently doing to ensure that it is a fully integrated and truly diverse campus?

BEGINNING INTEGRATION

Although Marlborough currently has a diverse student body and campus, the School did not admit African American students until 1972, 18 years after the Brown vs. Board of Education decision that mandated that all U.S. public schools integrate. In 1972, Marlborough hired a new Head of School, Robert Chumbook, who accepted the job on the terms that Marlborough would start accepting more diverse applicants, according to School Archivist Peter Chinnici.

The first class with African American students graduated in 1976 with three black students. Allison Banks ’77, who said that there were five African American girls in her class, said that she felt included in the community and that her race did not affect her experience as a student.

“I did not feel any different. I was welcomed in homes and on committees and in classroom discussions and I went on class trips. It was really no different at all,” Banks said.

Preimesberger echoed Banks’s sentiments.

“I just think it was the sense of sisterhood. I think that the traditions and the activities that we did really bonded us together. I think that…I just happened to luck out and be in a school with a lot of nice people,” Preimesberger said.

Banks noted that, during her time at the School, diversity was absent in the School’s faculty. She recalled that the only non-white faculty member was a Japanese American math instructor. Nonetheless, Banks said that growing up surrounded by black professionals allowed her to have role models to look up to outside of the Marlborough community.

“I could see that for others who may not have had the same upbringing and environment that [the absence of black faculty] would pose an issue. And, in retrospect, it would’ve been nice, but I don’t think it was an issue for me. It didn’t stop me from achieving; it didn’t make me feel less worthy of being there,” Banks explained.

Marlborough’s integration occurred as racial integration occurred in the country as a whole. In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court deemed the concept of “separate but equal” facilities unconstitutional during the Brown vs. Board of Education hearing. This ruling, however, only applied to public schools without addressing private schools. As a result, Marlborough remained a primarily white campus with no legal obligation to integrate. During the 1950s Marlborough enrolled a few Asian students, according to Chinnici, but the student population remained predominantly white. In 1966, Marlborough received its first application from an African American girl, but, according to Chinnici, “she withdrew her application somewhere along the lines.”

Some current students said they were surprised to learn that the School did not integrate until the 1970s, the decade after the peak of the civil rights movement.

“I guess being here at Marlborough and being in the culture, I’d want to assume that they’ve always been at the forefront of civil rights or…equality, but I never really stopped to think about it,” Victoria ’15 said.

WHY THE SILENCE?

Even though the past two decades at Marlborough have witnessed an emphasis on increasing and embracing diversity on campus, many remarked that the integration of the School is a topic rarely mentioned at an institution that often discusses its history.

Not only does there seem to be no written account of the integration, but students and administrators both remarked that questions about the School’s integration are rarely raised.

“It’s never been talked about,” Chinnici stated. He added that there is no actual written document that details the full story of the school’s integration.

As a result, the information that Chinnici has regarding the integration process of the School has been dependent on looking at old yearbooks and hearing stories from alumnae and former board members. This lack of specific details reflects the subtlety of the integration of Marlborough.

In October of 2014, the book An Ever-Enduring Spirit: Marlborough School 1889-2014, written by Judith Campbell ’65, was published to commemorate the School’s 125th anniversary. Although the book is full of stories and facts about the school’s history, the integration and diversity of the School do not appear within the book.

Wagner noted that she does not know why the integration of the School is something that is not talked about at Marlborough. Wagner suggested that the lack of documentation contributes to the lack of certainty and lack of dialogue about the School’s integration.

Lisa ’15, a member of OLE, mentioned that the school’s integration is something she has never thought about due to the strong presence of diversity discussions today.

“I have never really thought about a time when Marlborough wasn’t integrated because today the school offers so many opportunities to talk about diversity in large settings such as All School Meetings, but also offers us chances to talk about issues in small groups whether it be in the classroom or in various club meetings,” Lisa stated.

The absence of discussion about integration seems to contrast with the School’s recent emphasis on diversity.

When the School wrote the current Mission Statement in the 1990s, Marlborough addressed issues of diversity publicly for the first time. Wagner emphasized that, although all the different layers and kinds of diversity were not addressed specifically in the statement, the premise of diversity was prominent.

“That was a big move for the school at the time because, even though there were certainly issues, you know we were diverse in whichever way you want to slice or dice it, we weren’t ever saying that publicly,” Wagner commented.

However, the topic of diversity is becoming more and more prevalent each year. Along with English instructor Chris Thompson, dance instructor Mpambo Wina has chaired the Diversity Committee for the past five years.

“Our goal is to diversify the faculty and student body and do our best to make sure it’s an ongoing goal,” Wina said.

Wina explained that the School hopes to see the School embrace diversity in background and thought in addition to the more structural facets of diversity, such as race and class.

AN ONGOING CONVERSATION

Since admitting the first African American student just over 40 years ago, Marlborough has evolved in the way the School thinks about and approaches diversity. Recent efforts to promote diversity have furthered the objective of a fully integrated campus.

Over the last two decades, clubs have played an instrumental role in promoting diversity. Affinity groups celebrating diversity and culture first emerged with the African American Cultural Exchange (AACE) which was founded during the 1989-1990 school year. Other clubs with similar goals and models, like Exploring Asian Societies Together (EAST) and Organized Latina Exchange (OLE), followed shortly after.

Starting a club like AACE, according to Wagner, was a big move for Marlborough to make at the time, and the club helped Marlborough make strides toward building community.

“It seemed that it was important for people to get together around issues of identity,” Wagner said.

Today, these clubs work to bring attention to the groups’ presence on campus as well as to share the cultures of the different groups, according to both Peyton ’15, a member of AACE council, and Isabel ’17, president of OLE.

“[The goal] is to make the School aware of the different race groups we have in the School…and that we do have a say in how this campus works,” Isabel said.

Additionally, the annual Face-It retreat, class diversity retreats and speakers at All School Meetings who talk about issues surrounding diversity provide time and space for the community to talk about diversity and identity.

In addition to encouraging discussions within the student body, the School has turned its attention to promoting diversity in admissions and the hiring of faculty.

“I became aware that the School wanted to be [more diverse], and the School began significant outreach into the community to schools that were maybe non-traditional feeder schools,” Hotchkiss said of her return to the School as an employee and an alumna.

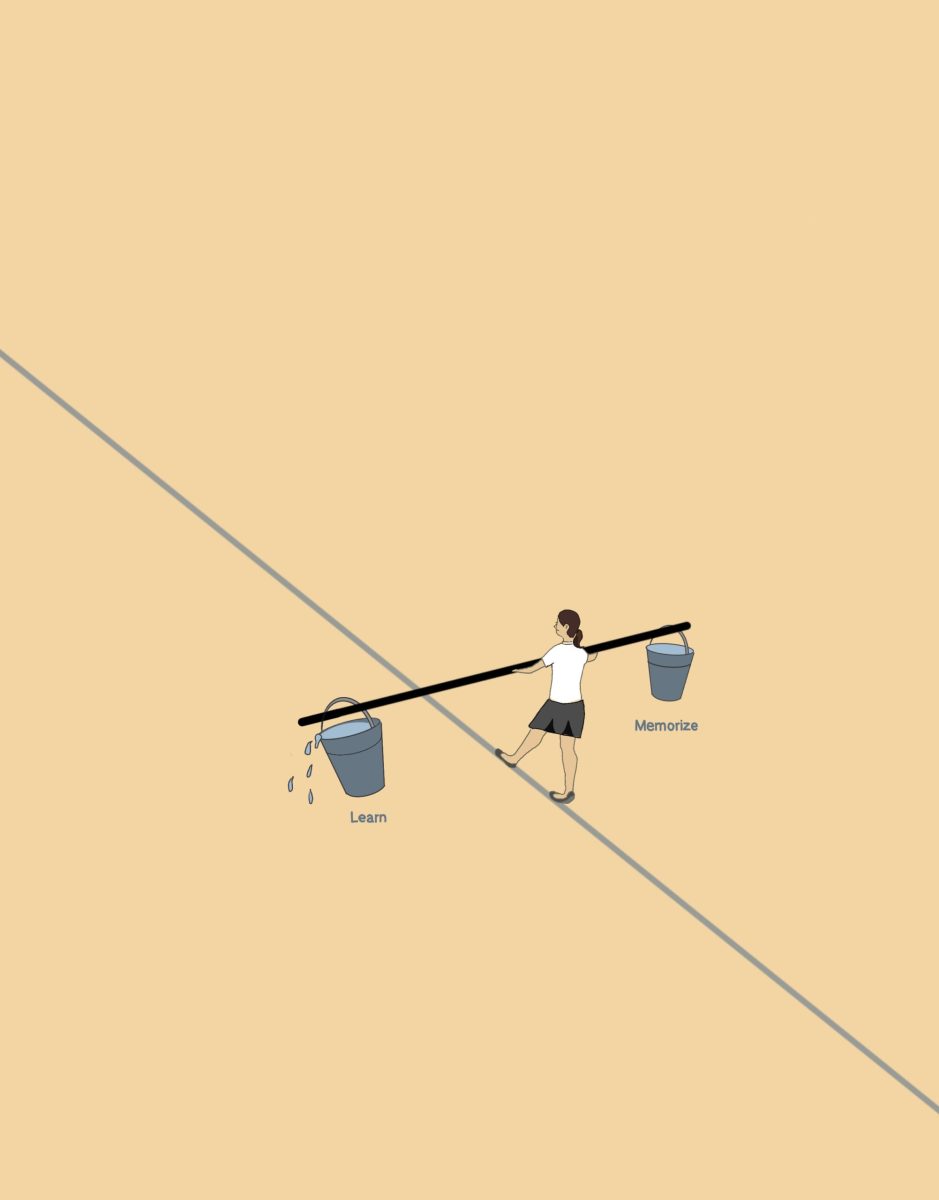

Wagner explained that Marlborough has widened its concept of diversity in addition to increasing efforts to promote it.

“In those early days, I think we were much more focused on racial diversity. And I think that today when we talk about diversity, racial is one component. But I think that now we speak equally about socioeconomic diversity and geographic diversity,” Wagner said.

Marlborough has come a long way, but there is still progress to be made in terms of the school’s diversity.

“There’s been a lot of progress over the years and [the School is] diverse, in a sense, but we still have so much work to do in regard to integrating, not even just race-wise, but across socioeconomic classes,” Peyton said.