Have you ever engaged with a piece of pop culture and felt guilty about it because of who made it? Before 2017, when Kevin Spacey was accused of sexual assault, did you used to say your favorite movie was “American Beauty” and have since changed your answer, even though it secretly still is? Is it the same with the album “The Life of Pablo?” Your feelings are probably the product of the predominantely online phenomenon known as “cancel culture,” in which prominent cultural figures are punished for accusations of problematic behavior ranging from sexual assault to a homophobic joke made on Twitter several years ago through the “cancelation” of their careers.

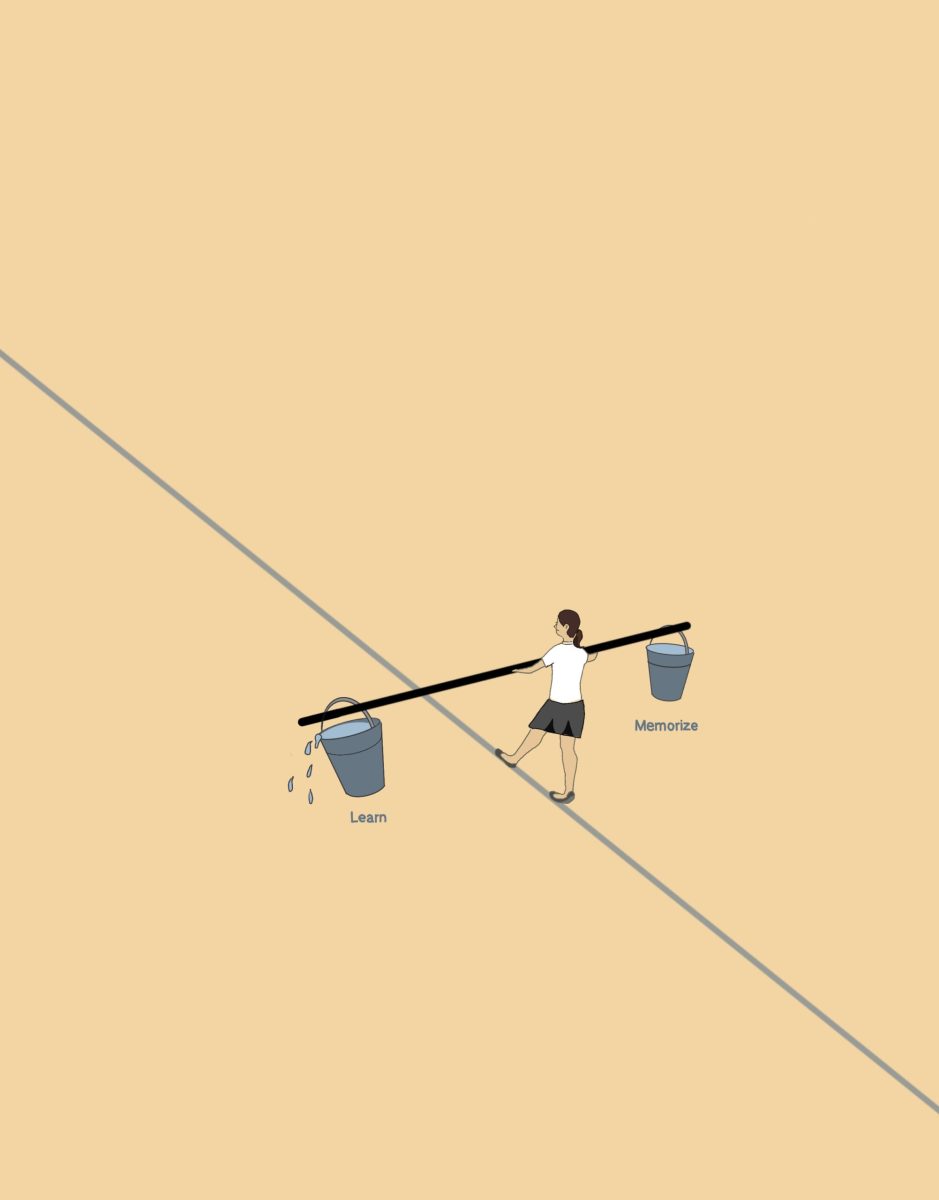

The driving force behind cancel culture is the belief that people in positions of power should be held accountable for their behavior, so limiting their cultural influence seems like the solution. One of the problems with “canceling” people is that by deciding that someone’s career is definitively over because of their action(s), we do not give people the chance to learn and grow; instead of conversation, they get cancelation.

I think that sometimes people do deserve to have their career ended for their actions. To me, cases of sexual assault should not be instances where the perpetrators should be given the opportunity to learn and grow. Sexual assault isn’t a mistake or brief lapse in judgement. A tweet, on the other hand, very much could be. Of course, a tweet could also be a reflection of much deeper ideologies or attitudes surrounding race, gender, sexuality, etc. However, sometimes it is just an ill-conceived joke with moral implications that are not harmless, but not encouraging of active discrimination against a group either.

I understand that words have real consequences, and jokes predicated on identity disrespect entire groups of people and contribute to the continuation of stigma surrounding an identity. However, cancel culture often does not evaluate or address each specific instance, and this system of accountability does not ameliorate the societal problems cancel culture really wants to target.

Another problematic aspect of cancel culture is that we even have to consider whether someone who tweeted something offensive should be punished in the same way as a rapist. When different cultural figures are canceled for doing different things with varying degrees of harmful consequences, their actions are equated, and I don’t think it’s fair to equate sexual assault with a homophobic joke—doing so makes the very legitimate goal of cancel culture seem unreasonable.

Additionally, whether or not you believe that people should be able to learn and grow from their actions, cancel culture is not the most effective method of accountability because once someone is canceled, they often do not stay canceled. The impermanence in someone’s cancelation is often due to the lack of consensus over whether their actions merited cancelation in the first place. But if we say a person is canceled and then shortly afterwards allow for the revival of their careers, it sends the message that their behavior can be excused again in the future and that, ultimately, their careers won’t have suffered all that much. “Cancelation” then doesn’t hold the meaning or weight it’s supposed to.

The question that prompted cancel culture in the first place is still relevant: How do we hold people accountable for their problematic actions and give them the opportunity to learn and grow, but also not give them the excuse to keep doing the same thing over and over again? Honestly, I don’t have the answer, but cancelling isn’t it. π