By Johanna ’17, Natalie ’16 and Julia ’15

One month before the planned Christmas release of The Interview, the Seth Rogen comedy in which two American journalists attempt to assassinate current North Korean dictator Kim Jung Un, Sony Pictures Entertainment suffered a crippling cyberattack that knocked the company’s operating system offline for weeks. On Nov. 24, employees received a disturbing message on their computers. Over a background of a skull, the screens read, “Hacked by #GOP,” with the statement, “We’ve already warned you, and this is just the beginning. We continue till our request be met. We’ve obtained all your internet data, including your secrets and top secrets.” In the following weeks, the Guardians of Peace (GOP), the group that claimed responsibility for the attack, leaked unreleased movies, executives’ emails and employees’ personal information, including health histories, payrolls and work reviews, in dumps of online data. Two months later, Sony continues to face legal and financial fallout from the hack that has both undercut the company’s reputation and shocked the cyberworld and general public.

In the 21st century, hacking has become one of the most important problems that corporations face with the threat of cyberattacks endangering both intellectual property and consumers’ personal information. According to 60 Minutes, approximately 97% of companies have experienced hacking of some sort, increasing the necessity of vigilant cybersecurity. According to Time Magazine, up to 56 million credit cards were potentially compromised in the Home Depot hack in November 2014, trumping the already staggering 40 million exposed in the Target hack during the peak of 2013’s holiday shopping season.

What kinds of attacks do companies regularly face? How has the Sony attack represented a shift in the field of cybersecurity? What cybersecurity challenges lie ahead for corporations?

CAUSES FOR CONCERN

As demonstrated by the variation in types of hacks, each attack has unique motivations behind it, but the majority of recent attacks have been focused on stealing consumer information, such as credit card numbers, or a company’s intellectual property. Many major corporations, from Home Depot, to Target to JP Morgan Chase, have been victims of hacks in the past few years, leading to the compromise of millions of customers’ names, passwords and credit card information. In late October, California Attorney General Kamala Harris said that over 18 million Californians experienced the loss of personal information to cyberthieves in 2013, an increase of 600% from 2012. While a surge in the volume of attacks has partially accounted for the rise, the large scale of the hacks towards Target and Home Depot has also contributed.

In addition to the fraud of customer information, companies face thefts of intellectual property; distributed denial of service (DDOS) attacks, in which hackers try to overwhelm a company’s website with data traffic and knock it offline; and attacks aimed at critical infrastructure, such as power lines or water treatment plants.

DDOS attacks can serve as a powerful tool for hackers or “hacktivists” looking to send a message rather than gain an economic benefit. Though they generally do not inflict permanent damage, DDOS attacks can still cause corporations significant setbacks.

“Some hacktivist groups, like Anonymous, have launched denial of service attacks in retaliation for policies that they don’t like. So if they disagree with a position a company’s taking or they don’t like something the U.S. government is doing, they’ll launch a DDOS attack against some sort of relevant website,” Kristen Eichensehr, a Visiting Assistant Professor at UCLA School of Law whose primary research and teaching interests are in cutting-edge international, foreign relations and national security law issues, said.

In what appeared to many experts as a DDOS attack in August of 2013, hackers shut down the NASDAQ for several hours. According to USA Today, an Iranian hacking group—Cyber Fighters of Izz ad-Din al-Qassam—claimed credit for the attack in an effort to make a political statement against the U.S.

Infrastructure hacks are not as common; however, one could potentially be catastrophic if it occurred on the same scale as consumer hacks have in the past.

“The same people who have gone onto the corporate network may not just be snooping around on the network in the future. They could actually do something really damaging,” Eichensehr said.

A SHOCK AT SONY

The November cyberattack on Sony Pictures Entertainment marked one of the most extensive and damaging attacks to date on a U.S. company, raising questions about the future of hacking and corporate cybersecurity.

In a dramatic departure from past thefts of intellectual property, the hackers did not look to steal the data unnoticed. Instead, they devastated Sony’s network, knocking the system offline. According to the New York Times, the attack destroyed three quarters of the computers and servers at the studio’s main operation, leaving the company scrambling for several days to secure its systems. Experts, including Jim Lewis, senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, predict that recovering from the attack will cost Sony up to $100 million due to the blow to Sony’s reputation and technology.

In addition to the magnitude of the breach, the Sony hack also stands out from previous attacks on U.S. corporations due to the hackers’ use of data leaks and the media to prolong and publicize the attack.

“We’ve seen thefts of intellectual property, but that intellectual property would sort of be kept for the hackers or for some purchase from the hackers. They wouldn’t post it out there for all the world to see. The Sony situation was something different,” Grant Davis-Denny, a partner at the law firm Munger, Tolles & Olson who often speaks and writes on cybersecurity issues, said.

In the weeks following the launch of the attack, GOP posted sensitive company and employee information online. According to Business Insider, the GOP claims to have stolen 100 Terabytes of data from Sony with the troves of data leaked accounting for only 235 Gigabytes.

Two months later, Sony continues to face consequences of the unprecedented attack. Court proceedings in cases stemming from the attack could plague Sony for years. In December, four separate lawsuits seeking class action status accused Sony of negligence for its cybersecurity policies. According to one suit filed by a former technical director at Sony Pictures Imageworks, Sony deliberately ignored the need to protect employees’ personal details in order to save money, leading to the leak of 47,000 current and former employees’ identifying information. The suit alleges that Sony kept passwords to company servers and social media accounts in files titled “password.” The plaintiffs have also pointed to comments from Sony’s former executive director of information security Jason Spaltro, who said in a 2007 interview with CIO magazine, “It’s a valid business decision to accept the risk. I will not invest $10 million to avoid a possible $1 million loss.”

CYBER CHALLENGES

As they seek to prevent and mitigate cyberattacks, corporations face the challenges of technological limitations, legal complications and insufficient cooperation between the private and public sectors.

The difficulty in defending against cyberattacks begins with technologically securing company systems against hackers.

“Cyber is an offense-dominant realm, so while corporations have to try to protect everything, hackers only have to pinpoint one weakness,” Eichensehr explained.

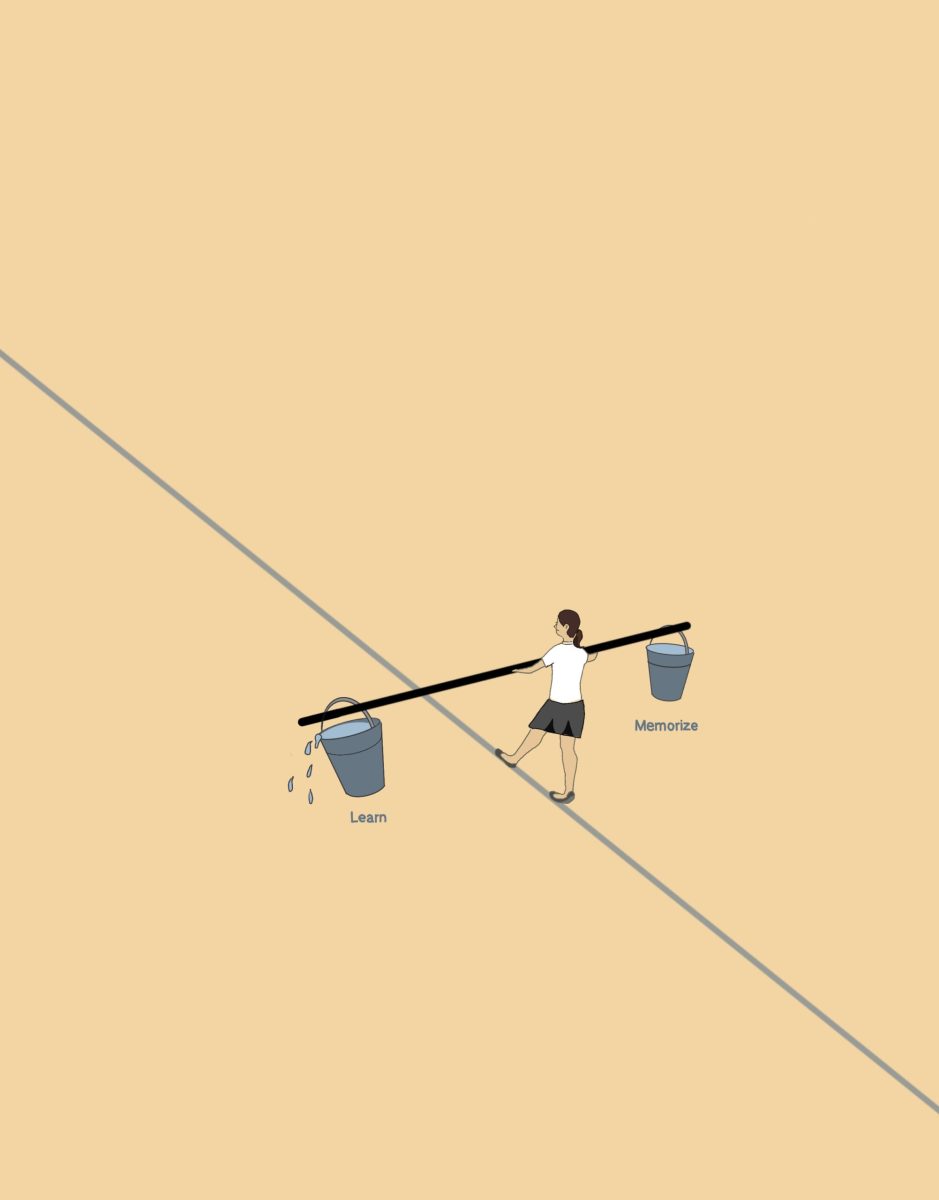

Employees for most major companies are required to learn how to operate their systems safely and effectively in order to prevent attacks from happening in the first place.

Manny Abascal, a partner at Latham & Watkins who formerly served as the Computer Crimes and Intellectual Property Coordinator while working as an Assistant United States Attorney in Los Angeles, believes it is necessary for corporations to not only use commercial security software and hardware but also to remind employees that they are accountable for preventing cybercrime.

“Training is important, and I think one thing companies may want to do is they may want to even test their own employees,” Abascal said.

Once a company suffers a cyberattack, companies must take steps in order to close the gap in their security and protect their customers and themselves. After addressing the breach in their system, companies may need to prepare themselves for lawsuits, as in the case of Sony.

“Prosecutors are focusing, if they can, on trying to prosecute the true bad actors here, which are the hackers themselves and not the companies that are the victims of the hacking attacks as much. The times when companies tend to get in trouble is when they don’t comply with their own cybersecurity policies or the representations that they made to their customers about the security of their data,” Davis-Denny said.

Davis-Denny also noted that there are certain legal obligations companies must meet in accordance with state laws, such as the notification of customers about the data breach, but he indicated that inconsistency across 47 different state laws can complicate the compliance of companies.

“One aspect I find interesting is that we don’t really have a national approach to cybersecurity in most industries…For most of our clients, who are nationwide companies, that could deal a challenge,” Davis-Denny said.

He explained, however, that partisanship and the rapid evolution of technology have thus far precluded congressional legislation from providing overarching standards for cybersecurity.

“The difficulty is to draft a law that would work for not just today, but five years into the future,” Davis-Denny said.

Eichensehr believes that one of the greatest issues in cybersecurity today is the balance between the role of the government and the role of the private sector in both deterring and responding to attacks.

“When you’re talking about the physical world, if you have a break in, you call the police, and the police investigate, and you sort of wait for the police to do their thing. In the cyber realm, companies I think are getting increasingly frustrated ….the government often is involved in these investigations, but the perpetrators of these attacks are often outside of the United States, beyond the reach of U.S. law enforcement,” Eichensehr said.

Abascal has witnessed increased information sharing and prosecution by the government.

“I think [the government has] been very proactive in alerting companies of activity they’re seeing so that companies can take measures to address problems. I think the government’s done a great job, and that’s certainly been something that’s improved over time,” Abascal said.

On January 16th, President Barack Obama and U.K Prime Minister, David Cameron announced efforts to end hacking threats by creating a joint cybersecurity unit between intelligence and law enforcement agencies. This is bringing the problem to a national level by putting cybersafety tension on display after the latest Sony attack.