Proposals for plastic straw bans as a cure for ocean pollution have gained mainstream popularity in recent months. This summer, Starbucks announced their plan to eliminate all plastic straws, while both Seattle and California heavily restricted single-use plastic straws in food service. Despite activists’ positive intentions, straw bans misdirect the limited and critically valuable pool of society’s moral outrage toward a comparatively tiny environmental problem.

The science surrounding the ban is notably inaccurate. Much of the current ban discourse stems from a statistic published in National Park Service reports and many accredited news sources including The New York Times that Americans use 500 million straws per day. Unbeknownst to readers, this figure was originally derived from research conducted by a 9-year-old who called just a few straw manufacturers to calculate an average in 2011. The statistic was widely discredited and recently shown to be almost three times too high by multiple consulting companies.

As it turns out, plastic straws have very little to do with ocean pollution. Scientists estimate that there are at most 8.3 billion plastic straws on coastlines globally. If all of those straws washed into the sea, they would comprise just 0.03% of the 9 million tons of plastic that enter the ocean every year.

By contrast, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, microplastics—small pieces of plastic that go down the drain from overwashing polyester clothing and using certain brands of toothpaste and face wash—comprise 30% of marine plastic pollution. Scientists have also found that at least 46% of plastic in the ocean is comprised of fishing nets primarily thrown overboard because ports lack disposal options. Fishing nets, though less glamorous, pose a far larger threat to the ocean than straws do. They clog up harbors and continue to catch millions of sea creatures yearly even after being abandoned.

The same energy put into the straw ban would yield far greater results if focused elsewhere. Consumer pressure related to dolphins getting trapped in fishing nets completely altered fishing industry practices in the 1990s. Similar outrage today could have the same effect on abandoned nets. Urging consumers to pressure corporations about the use of microplastics by boycotting certain products could also greatly diminish marine pollution.

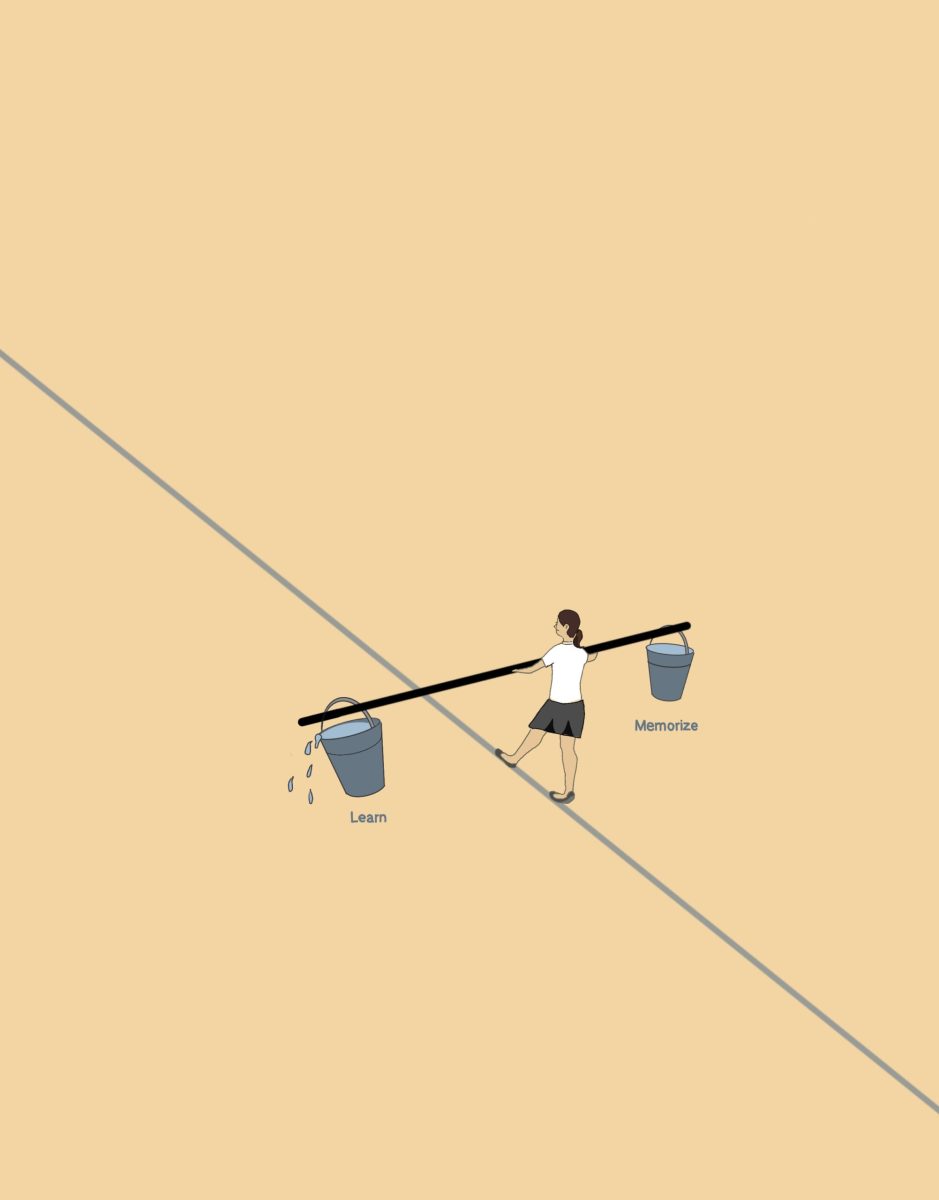

Some straw ban proponents argue that every little bit counts. This is true, but Americans have repeatedly demonstrated that they have both a limited attention span and limited moral outrage reserved for environmental issues. On top of this, the media has a limited appetite for environmental stories. It is essential that we maximize these scarce resources. In the face of imminent existential threats to our planet, the conversations surrounding straw bans just divert the public’s attention from more pressing problems like microplastics and nets.

Others argue that straw bans serve as a gateway to abandonment of single-use plastic. However, it is just as likely that the sense of moral high ground derived from the sporadic use of a metal straw could cause people to personally justify continuing to eat meat, buy fast fashion, travel on planes, avoid public transportation and engage in other habitual activities that cause environmental degradation. The culture surrounding plastic straw bans risks becoming a bastion of environmental hypocrisy and finger-wagging while yielding little tangible change.