By Rachel Carlson, Samantha Chung, Cameron Lange, Kendra Mosenson, and Noor Nouaili

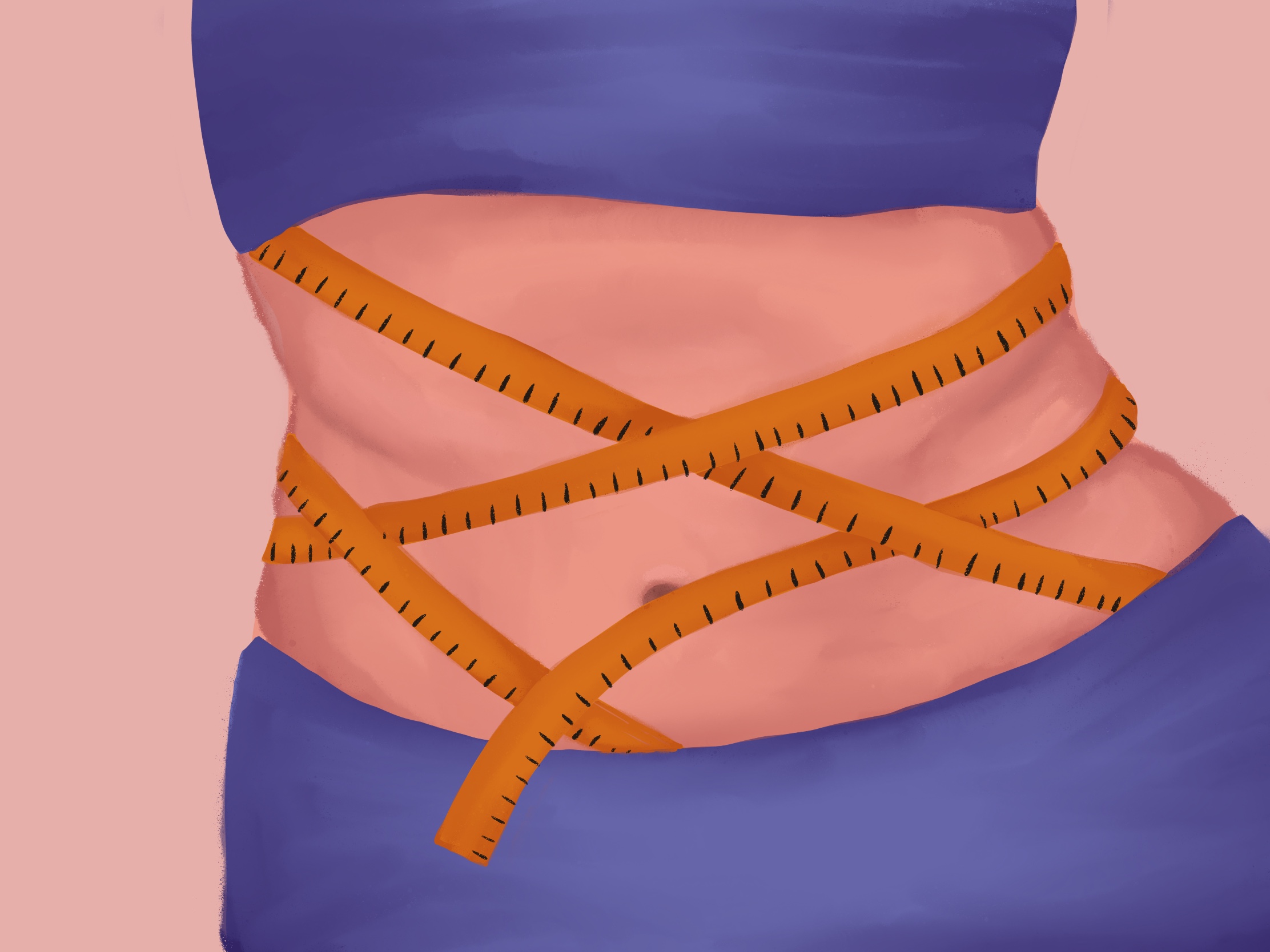

While no one is inherently self-conscious, as girls enter adolescence they are increasingly confronted by messages that instill a sense of shame in their bodies. According to the University of Washington, 53 percent of thirteen-year-old American girls claim to feel “unhappy with their bodies,” and by age 17 this figure grows to 78 percent. Even at age 10, 81 percent of girls feel afraid of being fat. Various factors play a role in this phenomenon. The popular media has increasingly idealized thin female figures since World War II, reflected in the choice of thin, Photoshopped models who were featured in advertising campaigns by many major companies. Some suggest that a crisis in perceptions of body image has swept modern society, disproportionately affecting teen girls, who a Yahoo Health survey sampling a nationally representative group of 2,000 people found to be 3.5 times less body-positive than their male counterparts. In a survey of 3,452 women conducted by Psychology Today, 24 percent of women said they would trade more than three years of their lives to achieve their weight goals, while 15 percent of women said they would trade more than five years.

Consequently, a lack of body confidence has harmful effects on people’s lives. One quarter of teen girls with low self-esteem have altered eating habits, compared to 7 percent of girls with high self-esteem. Further, one quarter of teen girls with low self-esteem resort to self harm, compared to 4 percent of girls with high self-esteem. This data is particularly significant when considered with the data showing that the teen suicide rate in America has increased over 70 percent from 2006-2016 as suicide came to replace homicide as the second-leading cause of death among teenagers, according to CDC data. Many experts suggest that exploring the root causes of poor body image may be key to addressing the issue.

Media

Girls today witness the the objectification of the female body in media such as advertising, film and television, which has ramifications for their perceptions of their own bodies.

According to a Kaiser Foundation Study, 58 percent of female characters in films have comments made about their appearance by other characters, while this holds true for only 24 percent of male characters. Health and Wellness Instructor Nicole Beck said these unrealistic expectations for girls and women from media can be dangerous to self-image.

“Media is manipulated to show women to look a certain way, but the message is that you have to be smart, you also have to be kind, you also have to be accommodating, but you also have to look like a perfect 10 model all the time, which is just not realistic,” Beck said.

The objectification of women and their bodies in the media is an issue that reaches farther than just film and television, as the female appearance is exploited by large companies for commercial purposes. The same Kaiser Foundation Study found that 50 percent of the advertisements directed at women use the appeal of beauty to sell their products, and that one in every three articles in leading teen girl magazines also includes a focus on appearance.

At the STRIPED (Strategic Training Initiative for the Prevention of Eating Disorders) program event at Harvard, Jean Kilbourne, an activist who focuses on finding connections between advertising and mental health, said the advertisement of beauty is so extensive that 50 percent of three- to six-year-old girls worry about their weight. In her film series “Killing Us Softly 4: Advertising’s Image of Women,” Kilbourne explained that advertising companies have moved past just selling their products, and that they now sell a lifestyle as well.

Miranda Simon ’20 also believes that beauty has become more important than health and wellness in sales.

“American consumer culture has become so focused on female beauty that it’s considered to be as much of a selling point as the products themselves,” she said. “It makes me sad because companies should be able to sell products simply as products that benefit people instead of losing their original vision because they need to appeal to commercial expectations.”

Beck said most teenagers feel insecure about their bodies for a variety of reasons, but they should remind themselves that there is no one way the female body should look.

“It is so important to understand that what is being shown to us in the media has been manipulated in order to look ‘perfect’ in many layers: first, females whose job it is to be thin often times do not have healthy eating habits; second, the female body is altered through Photoshop and other photo-modification softwares,” Beck said.

In order to combat the manipulated images of women that advertisers use to sell their products, many organizations have begun to launch body confidence initiatives. Recently, Dove––a personal care brand––launched the Girl Collective, a self-described sisterhood that builds body confidence and challenges beauty stereotypes for all women and girls. Additionally, in 2015 a clothing company called Lane Bryant created the campaign #ImNoAngel, a series of commercials starring plus-sized models explaining that any body shape can be beautiful, indirectly referencing Victoria’s Secret Angels.

In an essay entitled, “The More You Subtract, The More You Add,” Kilbourne explained that companies take advantage of the insecurities of young women in order to sell their products.

“Fashion advertising often sells more than fashion. My hope is that enlightened people in the industry will be more careful about what else they are selling, about the messages they are perhaps unwittingly conveying to girls and women (and boys and men too),” Kilbourne wrote.

Although some companies have been taking steps to promote a healthier body image, Arin Littman ’20 said there is still a lot of work to be done.

“As long as somewhere in the world a commercial is playing in which a beautiful model poses while the object she is actually trying to sell floats around somewhere in the background, media has a long way to go before it succeeds in making young women feel more confident about their bodies,” Littman said.

Modeling industry

Women also find themselves expected to conform to strict, often unattainable standards of beauty set by popular female fashion models.

According to “Plus Model Magazine,” the average female model weighs 23 percent less than the average woman. The fashion industry typically requires models to be 5’8” or taller, though 5’4” is the average height of American women. In addition, racial diversity is often underrepresented in the modeling industry and contributes to body image issues among women of color.

Dance Instructor Mpambo Wina explained the pressure women feel to look like the models they see in media.

“If you look at fashion models, they tend to be tall because the clothes have to drape on them to a certain degree,” Wina said. “You are going to find people who are drawn to what they consider the epitome of beauty for that kind of woman. And I think for young girls who look at that, they may feel as though they do not fit those exact beauty standards.”

Stores like Brandy Melville contribute to this pressure with their “one size fits most” fitting guide. In reality, Brandy Melville’s one size does not fit most—it fits tall, thin body types.

Beck agreed that models’ appearances reflect a lifestyle that most women cannot replicate.

“If it is someone’s profession to look a certain way, they would have a team around them to help them work out, eat in a way to stay thin and possibly even have surgery,” Beck said.

In recent years, the modeling industry has begun to feature more diversity. According to the New York Fashion Week Diversity Report, 37.3 percent of women who walked the runway at in Fall 2018 were women of color, as opposed to 20.9 percent in Spring 2015.

Wina believes an increase in diversity is vital in encouraging positive body image among women and girls of color.

“The more people see people in the media that look like them, I think that helps to alleviate any feeling of isolation,” Wina said. “It helps to alleviate any feeling that they’re not enough.”

Although the modeling industry has expanded to include more racial diversity, 30 percent of models in Fall 2018 were plus-size, representing an 8 percent drop from Spring 2018.

“Being more inclusive is not only limited to diverse skin color, but also non-binary expression and varied body shapes,” Beck said. “Women are multi-faceted beings, yet media portrays them one-dimensionally, and that adds to the objectification of women.”

Family

Not only does modern media significantly affect girls’ perceptions of body image, but parents and other family members can also influence young girls’ feelings about their bodies.

As Edina Hartstein ’19 left her house as an eighth grader to attend a football game with one of her Marlborough friends, she said she remembers her dad suggesting she straighten her hair and put on makeup.

“I don’t think I’ll ever forget that,” she said.

Beck said parents and families play a major role in their children’s perception of their bodies and development of body confidence.

“It can start at a young age: making comments about a young girl’s weight, appearance, and size will influence how they feel about themselves later in life,” she said. “Behavior at home that is modeled for children embeds in their brain, so everything from gender roles to relationships to food will make their mark on a girl’s body image.”

Ava Richards ’19 said parents may underestimate the ways in which comments about their children’s bodies impact the way their child sees themselves. She also said Marlborough students may not only feel internal and external pressure to succeed academically, but also to meet certain beauty and appearance standards.

“We expect kids to be such high functioning individuals, and with that comes a lot of pressure surrounding appearance,” Richards said.

Richards added that one way for parents to combat this pressure is to engage in non-critical dialogue with their children about the images presented to them in the media.

“You can’t control what your child sees in the media, but you can certainly talk to them about it and about how unnatural depictions of women in the media are,” Richards said.

Additionally, parents and their children might have different opinions about body diversity.

“If you think back on a parent’s upbringing or their high school years or junior high school years, [pop culture] was probably different than it is now in terms of the diversity of magazines and the media and everything else,” Wina said.

In addition to having conversations about the media, Director of Educational and Counseling Services Dr. Marisa Crandall said families should encourage lifestyles that include healthy eating and activities as an alternative to comments about physical appearance.

“The best thing you can do for your child to give them body confidence is to get them moving, for you to be active yourself, and to do active things with your child so that they will develop a healthy lifestyle,” Crandall said. “The other thing that parents can do is be accepting and positive about their own bodies, as well as their children’s bodies.”

Julia Song ’20 agreed that fostering body positivity is an important goal for teenagers.

“Body image is an issue that affects everyone. With all the pressure to look perfect these days, we should strive to reach a place of understanding of one another and appreciate that we are all beautiful in our own ways,” she said.