In the midst of a discussion regarding the phallocentric order (just your typical day in Honors English Seminar), I glance around the room to see several of my peers’ eyes darting at phones in their laps, their fingers grazing the screens. I myself have not become immune to this instinct—when my phone vibrates in my backpack, I twitch to check what message I have received—but it saddens me that, when given the opportunity to engage in discourse at such a high level, students would rather pay attention to a mechanism instead of to an output of ideas.

Frantic phone-checking is not relegated to one classroom or subject; the Pavlovian response—a conditioned response to an external stimulus—discriminates against no branch of academia. It’s more noticeable, however, in an intimate classroom of eight people discussing philosophy than in a math lecture of twenty. Part of Marlborough’s appeal to my young, not-yet-exhausted mind was the prospect of small classes where intellectual conversation and chin-stroking could flourish, and while I haven’t been disappointed, it’s not nearly as fun when a quarter of the room is fixated on Facebook.

I’ve come to the point where I can see the appeal of the smart phone’s omnipresence. Before the rigor of first-semester senior year sapped me dry, I refused to even bring my phone to school most days, afraid of losing my focus. But now I’m infected with senioritis, and I get it: phones are pleasant things to look at, taking up much less brainpower than lofty theories of literature or derivatives. It’s hard to be “on” all the time, every single day, and scrolling through Instagram somehow eases the aches that come with sentience, the all-too acute awareness of being alive. At the same time, I yearn to go back to being hyper-aware in the classroom, and I can’t help but feel I (and, if I’m to be so presumptuous, my fellow classmates) have lost some vigor and clarity to the lure of the iPhone’s base pleasures.

While this affliction proliferates in senior year, we can avoid its beginnings by also cutting phone time for students in the earlier grades. While I don’t condone censoring things for the sake of young’uns (who, by the way, know way more than we give them credit for), I believe that it is important to monitor their phone activity not because of the content they can find but to foster good concentration habits that will follow them into the Upper School and beyond. If I had anything more than a barely functioning flip phone in 7th grade, I would probably be a dead-eyed automaton by this point.

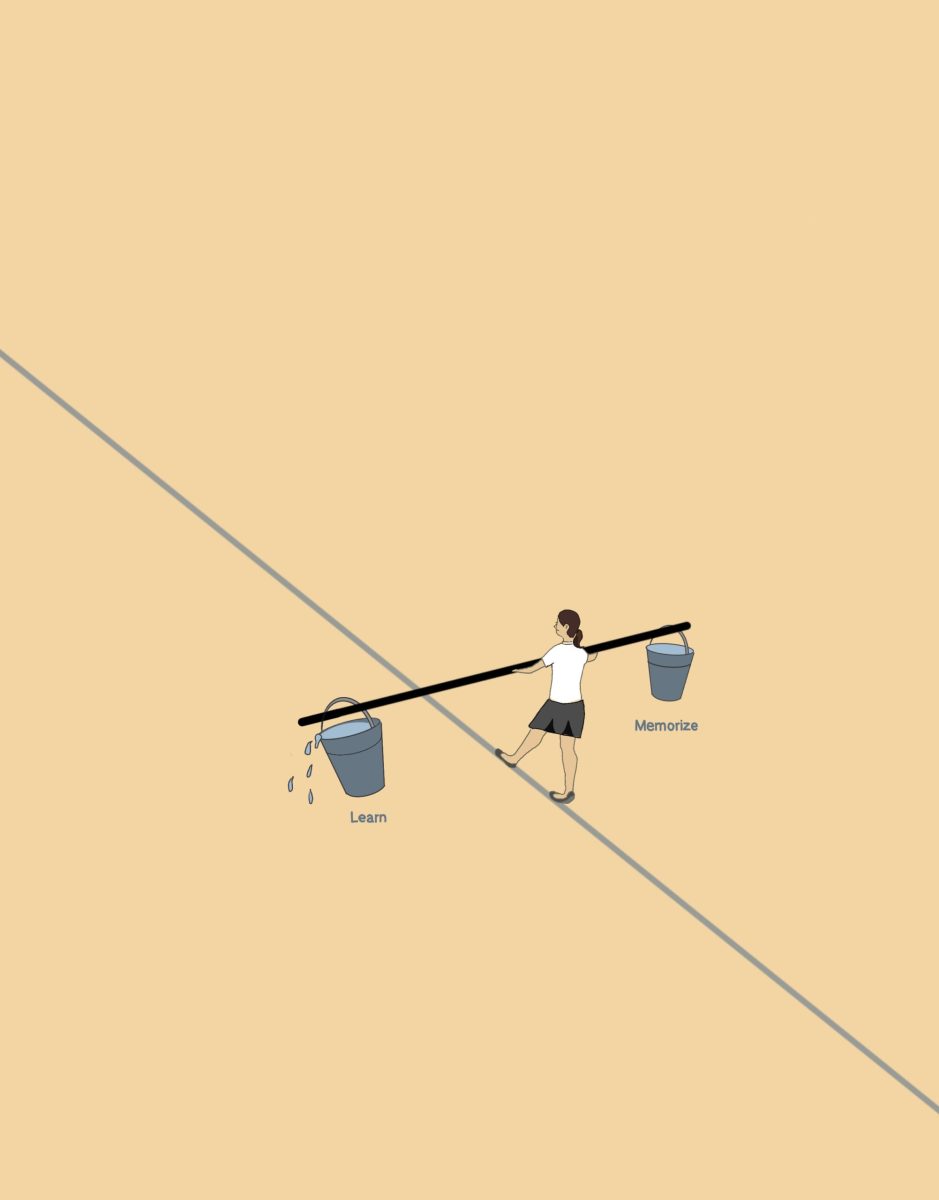

Turning off phones in the classroom will not only better facilitate discussion and overall focus but also sharpen the mind in general. With the implementation of the one-to-one program next year, I foresee technology becoming even more of a presence in the School than it already is, so by limiting superfluous devices like phones, the abundance of wires and gadgetry will seem less overwhelming. I suggest that during 75-minute classes, teachers should give short breaks so everyone can check their phones then and be able to concentrate more in the rest of the time period. Students will inevitably make more eye contact and pay more attention to the subject at hand, creating a livelier intellectual environment while also improving retention of information and lifelong focusing skills.