On Apr. 24, 2013, the Rana Plaza garment factory in Bangladesh collapsed. The tragedy, in which 1,100 garment workers lost their lives, exposed the lengths to which manufacturers and factory owners will disregard labor and safety requirements and exploit their workers in order to keep clothing inventories overflowing with on-trend clothing items at cheap prices. This horrific incident in Bangladesh shed a negative light on the fashion industry as a whole by providing insight into the lives of the individuals behind the sewing machines in some of the world’s most impoverished countries and exposing the often selfishly ignorant mindset of American consumers. The episode revealed terrible working conditions, overcrowding and extreme safety hazards that are ignored due to sheer convenience and ease.

According to NPR, “fast fashion” refers to inexpensive clothes that are produced in the fastest possible way to mimic current luxury fashion trends. Many factors have contributed to the rise and dominance of fast fashion, but among the most prominent are globalization, increased industrialization and technological innovation. While it is difficult to pinpoint exactly when and where the practice of fast fashion began, it is clear that the idea is heavily embedded into the minds of American consumers. The trend of cheap, disposable clothing that is mass produced overseas seems fairly recent. A 2011 ABC News study found that approximately 98% of the clothing purchased in the United States was imported from abroad, compared to a mere 41% in 1995. Additionally, a survey by the American Apparel & Footwear Association found that in 2013 the average American bought 68 garments and seven pairs of shoes a year, which is twice as much as the national average in 1991.

According to US News & World Report, “fast fashion has created a culture of disposable clothing, which exploits low-wage workers in other countries and is environmentally unsustainable.” Stores such as H&M, Forever 21, Zara, Old Navy and The Gap constantly turn over their merchandise to make room for newer, trendier clothing and to appeal to the young and fashionable consumer.

“We want to surprise the customers,” says Margareta van den Bosch, H&M’s style adviser, in an NPR interview aired in Mar. 2 0 1 3 . “We want to have something exciting. And if it’s all the time hanging the same things there, it is not so exciting.”

Although the benefits of fast fashion include stylish, low-cost clothing and a huge increase in both productivity and employment, its downsides include the exploitation of low-wage workers in foreign countries, an increase in counterfeit and fraud among big business executives and an exponentially greater increase in damage to our environment.

Although single-use goods are not a new concept, the rapid expansion in fast fashion has impacted the planet. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, Americans throw away about 12.7 million tons of clothes every year, which is an estimated 68 pounds of clothes per person. Increased demand for factories creates increased air pollution, exacerbated by little to no pollution regulations at most factories around the world. Lastly, fast fashion depletes our water sources, promotes the use of harmful chemicals and increases our use of fossil fuels.

Fast fashion also raises a heavily debated ethical dilemma. As China’s economy rapidly developed and expanded to over 40,000 factories in the late 1970s, Chinese factory workers demanded higher wages. This led fast fashion companies to move their production to places with even lower wages, like Bangladesh. At its core, the cheap labor provided in developing countries such as Bangladesh and Vietnam enables companies to exploit factory workers, paying them $38 a month, for example, for hours of labor-intensive work. These factories are often poorly structured, overcrowded and unsanitary with plenty of room for disasters, as shown by the Bangladesh tragedy in 2013.

Journalist and author Elizabeth Cline decided to investigate the phenomenon of fast fashion, and her recent book Overdressed explores the way in which fast fashion has transformed our attitudes about the world in which we live.

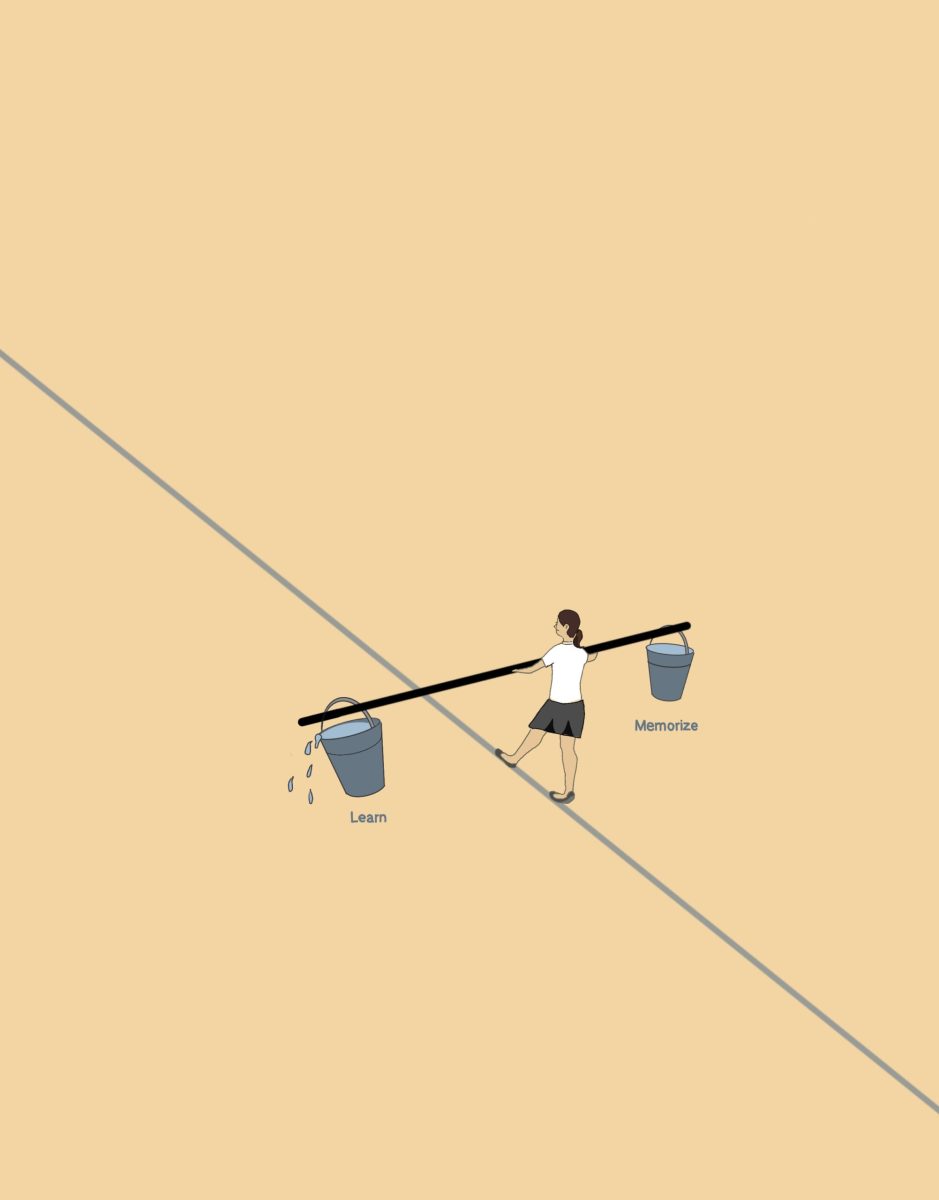

“[Fast fashion] has really changed our relationship to clothing. We no longer really go out there to buy things that will last. We kind of walk into an H&M knowing that what we’ll buy for under $50, for even $15, may not last, may fall apart in the washing machine, you may only wear it once, but it’s OK because you’ve spent not so much money on it,” Cline writes.

She adds that, because the products are cheap and the designs are attractive, for most customers it’s “virtually impossible to walk out [of a clothing store] empty-handed.”

For most Americans, the issue of fast fashion is a double-edged sword. Steering away from fast fashion chains and purchasing, fewer, more expensive clothes of better quality seems like a perfect solution. However, the majority of Americans cannot afford anything more expensive than the $10 t-shirts they purchase on a regular basis, even though they may be compromising quality and encouraging the corruption of the production process.

“If people can’t afford better, shop where you’re going to shop. Sometimes it’s about how you shop and not where you shop. So if you buy something cheap, that doesn’t mean that you have to have a disposable attitude to it…or a disposable relationship to it,” Cline writes.