In recent weeks, the change.org online petition “Bring Back Nigeria’s 200 Missing School Girls #BringBackOurGirls,” which has been “signed” by over 900,000 supporters, has been bouncing around on social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter. This type of online social activism–signing a petition or posting about an issue on social media–is now the norm. In the information revolution of the 21st century, social media has transformed social activism into digital activism, or, what some have come to call “clicktivism.” Clicktivism is defined as the use of social media and other virtual tools to advance a cause.

While clicktivism can be used to organize physical protests in addition to gathering data-driven support, the main issue critics cite with the phenomenon of digital activism is the instant gratification people receive when participating in online movements, without having to truly contribute to the movement itself. In other words, people can feel good about themselves for doing essentially nothing.

In his October 2010 New Yorker article “Annals of Innovation: Small Change,” Malcolm Gladwell cites two cases of social media-led movements. The first was the 2009 “Twitter Revolution” in Moldova, where thousands protested in the streets against the country’s communist government. The second example was the student protests in Tehran. According to Gladwell, the problem with these two social media led revolutions was that, in Moldova, Twitter accounts are scant, and those tweeting about the Iranian demonstrations were largely based in the West.

Gladwell’s article was written just before the official start of the Arab Spring in December of the same year. The world had not yet seen the series of domino-like revolutions that rolled across the Middle East.

During the Arab Spring, social media enabled people around the world to hear about the revolution, empowering some people in neighboring nations to start their own revolts. Social media inthe Arab Spring was used by the protesters to coordinate action and to provide sources of information not controlled by ruling regimes.

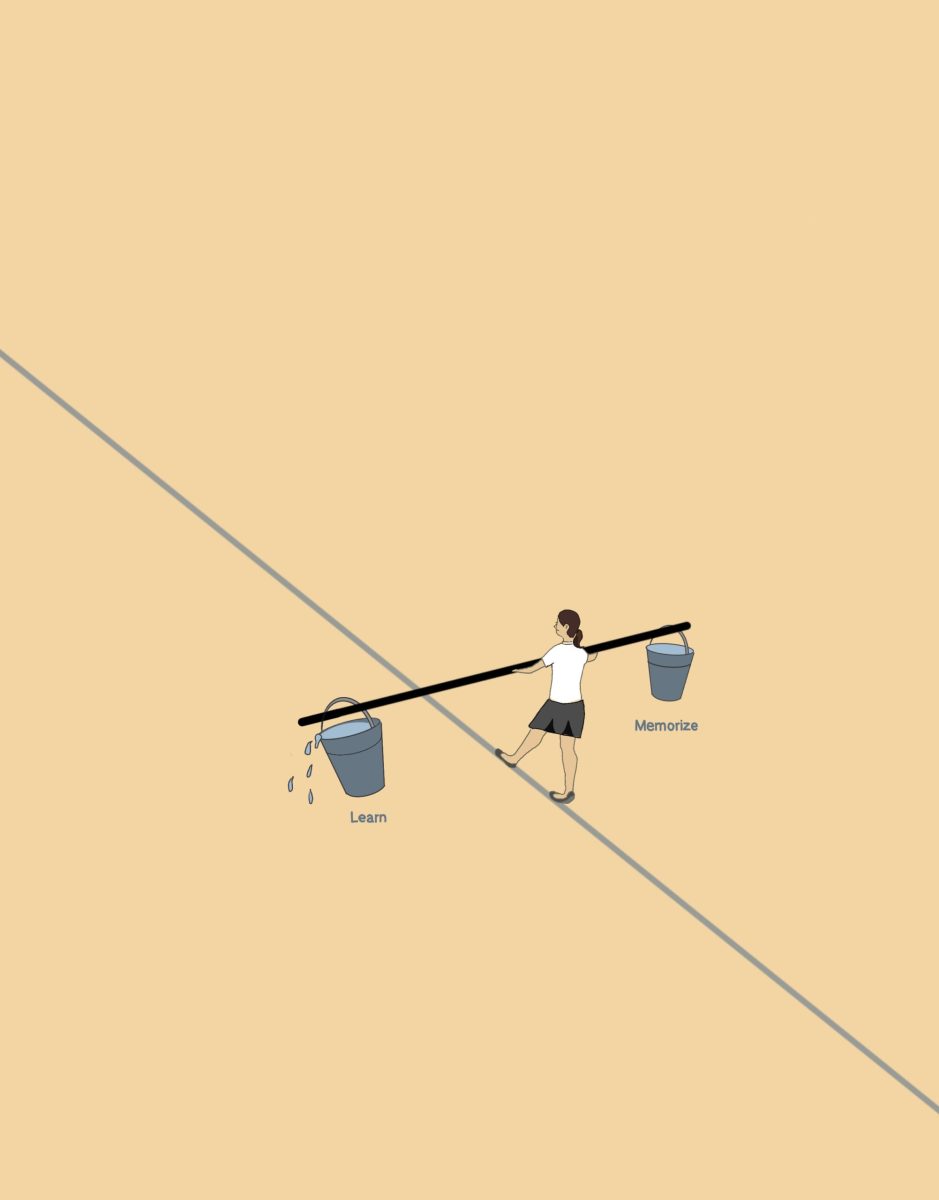

Gladwell argues that “social networks are effective at increasing participation—by lessening the level of motivation that participation requires,” and goes on to state that only physical “high-risk” activism is truly potent, because it creates strong bonds between people, whereas online activism fosters “weak-tie connections.” Furthermore, he explains that because social media-based activism lacks hierarchical organization and centralized authority, it is less effective than in-person activism.

I agree that this is true in some respects. Weak connections are indeed the main problem presented to groups such as Anonymous, which are chaotic collectives rather than organized units. However, we must not underestimate the power of quickly mobilized mass support. Having the ability to communicate freely with others is immensely valuable. Social media allows for the speedy creation of networks that span continents.

Furthermore, the emergence of social media as a significant player in modern-day activism does not mean the total death of activism as we know it. Rather, as we’ve seen during the Arab Spring, social media can be used to organize physica, in-the-flesh protests on the streets. Virtual acts of protest or support do not wholly replace physical activism: instead they work together to form a new hybridized kind of activism.

Even forms of online activism that exist solely on the Internet have been successful in putting pressure on specific groups. In the case of the kidnapped Nigerian school girls, the online petitions drew so much support that public opinion pushed the United States government to recently agree to share “intelligence and provide investigative help,” according to The Los Angeles Times.

For this reason, I think it is unproductive to scorn methods of activism that have proven to be successful, and I think efforts should instead be focused on finding the strengths of the new tools at our disposal and investigate ways to put them to good use. Ultimately, those who fight for social good are not going to be dissuaded from acting simply because they can more easily sign a position or retweet a catchy hashtag. Those who feel satisfied that they have done as much as they should to change the world for the better simply by clicking a link would probably not have taken to the streets or participated in sit-ins back in the pre-Internet era. And if that is true, the more people who are informed or voice support of a cause, the gesture, no matter how small, is better than nothing.