Seventy years after South Carolina electrocuted 14-year-old African-American George J. Stinney, Jr. for the alleged murder of two white girls, his family is seeking exoneration through either a new trial or a voided verdict, which would clear Stinney, the youngest person to be executed in the United States in the last century of the crimes.

A lack of evidence and an acknowledgement of Jim Crow-era prejudices place Stinney’s supporters in a hopeful position for redemption, even though a new trial has not yet been granted. Although Judge Carmen Mullen of the Fourteenth Judicial Circuit Court in South Carolina declared at the beginning of the preliminary hearing, which began in late January, that she would not address Stinney’s guilt or innocence, the case imbued the hearing with a trial-like atmosphere. (A hearing can address anything that needs to be settled before a trial, such as whether or not a piece of evidence is admissible. A trial, on the other hand, presents evidence to a jury that decides the outcome of the case.)

After Betty June Binnicker, 11, and Mary Emma Thames, 7, did not return home one afternoon in March, 1944, Stinney and his father joined a group that was searching for the two girls. Shortly after the search party found the girls’ bodies in a ditch, having been beaten to death by railroad spikes, someone said they’d seen Stinney talking to the two girls earlier that day, and Stinney was arrested for their murders.

Stinney confessed to killing Binnicker and Thames, but child and adolescent forensic psychiatrist Amanda B. Salas said that Stinney’s admission was “a coerced, compliant, false confession.” According to the New York Times, Salas “attributed the confession to his vulnerability as a black teenager facing scrutiny by white officials.”

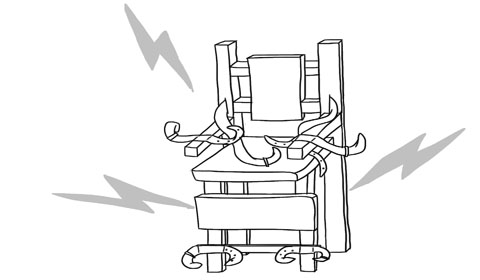

Stinney’s trial lasted an hour, and the all-white jury took just ten minutes to decide the guilty verdict. The 14-year-old faced the electric chair without further questioning.

According to Amie Ruffner, Stinney’s sister, the jury “used my brother as a scapegoat.”

The only news coverage from the time of the case is a two-sentence clip from the New York Times, dated June 12, 1944 from Sumter, South Carolina. The clip, entitled “Asks Sparing of Negro, 14,” mentions that the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was protesting to the Governor of South Carolina against Stinney’s scheduled execution. The second sentence merely states, “George J. Stinney of Alcolu was convicted of the slaying of one of two girls beaten to death with a railroad spike.” The ultimate conviction, however, was for the murder of both girls.

There were no witnesses in the 1944 case. Virtually no evidence remains (and the existence of evidence at the time of the incident is unclear), and many of the records have been destroyed. Additionally, the recent hearing has raised questions about the limits of memory. University of South Carolina School of Law professor Kenneth Gaines said to the Huffington Post that “South Carolina has strict rules for introducing new evidence after a trial is complete, requiring the information to have been impossible to discover before the trial and likely to change the results.”

Although the request for a new trial is largely symbolic, in that a pardon for Stinney’s name would be a dignifying statement against the potentially unjust 1944 ruling, Stinney’s supporters want the case to be actually reopened, so that Stinney’s can be legally exonerated.

“I’d like to see them find him innocent,” said another of Stinney’s sisters, Katherine Robinson.

Frankie Bailey Dyches, a niece of one of the murdered girls who was born after Stinney’s execution, said, “[Stinney] was tried, found guilty by the laws of 1944, which are completely different now – it can’t be compared – and I think that it needs to be left as is.” While Dyches does not support the reopening of Stinney’s case, she acknowledges that justice in the Jim Crow South, when an African-American teenager charged with the murder of two white girls went up against an all-white jury and was essentially tried as an adult, should not be compared to the justice system today.

A new trial of the Stinney case could not be decided simply based on the fact that, today, the death penalty only applies to adults, but shifts in people’s mentalities since 1944, regarding both race and the capital punishment of juveniles, could certainly affect the verdict.

CAPITAL PUNISHMENT

Juveniles and the Death Penalty

- The U.S. Supreme Court barred the execution of juveniles in Roper v. Simmons (2005). Prior to the Court’s overturning, 19 states with the death penalty did not allow the practice to apply to juveniles.

National Consensus (Prior to Roper v. Simmons)

- No juvenile death penalty in 31 states, including California

- No juvenile offenders executed since 1976 in 43 states, including South Carolina

Current Methods for Execution

- South Carolina: Allows prisoners to choose between lethal injection and electrocution

- California: Provides that lethal injection be administered unless the inmate requests lethal gas

Wrongful Executions

- According to an 1835 article from the New York Times, “A new study on capital punishment in the United States asserts that in this century 343 people were wrongly convicted of offenses punishable by death and that 25 were actually executed.”

- Evidence suggests that 4 men may have been wrongfully executed in the past two years.

Race and the Death Penalty

- According to a 1990 report from the General Accounting Office, the race of a murder victim was found to influence the likelihood of the offender being charged with capital murder or receiving the death penalty; the offender was more likely to be sentenced to death if the victim was white than if the victim was black.