It’s Saturday night, and glorious free time stretches before you like a lush meadow. You snuggle into your pajamas and slide in a DVD. A few cinematic foibles and some laughs later, you’ve begun to unwind and enjoy. But soon you find yourself cringing every few scenes as the shrewish wife berates the male protagonist, or the “quirky” girl exists solely to bring the boy out of his funk, or the women’s lives all revolve around their men. Still, you admit sheepishly, you are entertained.

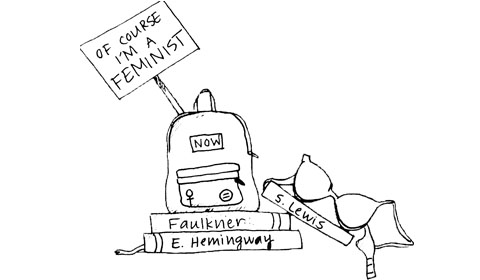

Until recently, this scene occurred on a regular basis for me; as an avid reader and moviegoer, I struggled to reconcile my love of the arts with my feminist principles. Stories that I loved as a naive child often appeared, in retrospect, startlingly sexist, yet I did not want to let go of my fondness for them. (Don’t get me started on Disney princess movies!) I was at war with myself, feeling constantly stressed while doing something that should have felt relaxing. And then I realized that these two sides, feminist and movie lover, could coexist.

This summer I read the book From Reverence to Rape: The Treatment of Women in the Movies. At one point the author Molly Haskell writes, “I consider myself a film critic first and a feminist second.” Upon reading that sentence, I let out a resounding cheer; I knew that that was how I needed to see myself as well, because if I constantly analyzed every female character, I would ruin the story, and yet I could not bypass misogyny.

As we well know, over the millennia, men authored the bulk of the world’s famed texts about women, ranging from Aristophanes’s Lysistrata to Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina. Women were muses for authors more often than they were authors themselves. Of course, as we can tell from the writings of Sylvia Plath and Emily Dickinson, the dearth of female voices is not due to lack of talent but to the patriarchal structure of most societies. So, undoubtedly, many of the classic books we read, plays we see, and films we watch stem from male minds, and while they may be of high quality, they more often than not do not present women as well-rounded characters or central figures. Or, when writers do feature women, the female characters seem to be central only to a romance.

And what is wrong with romance? Well, nothing inherently. I myself enjoy a good romantic story. (Harold and Maude, anyone? No? Okay, your loss.) But when a woman can only play a prominent role in narratives that solely have to do with her relationships to men, then something’s amiss. Beyond that, though, endless heaps of romances are yawn-inducing; women think of things besides romance. We have existential crises and parental issues and psychedelic road trips à la Easy Rider, too.

I know this observation of womanless or romance-heavy storylines sounds cynical, and there definitely are exceptions, but do you see my dilemma? Much of the art I love is from the past, but its composers do not exactly present women as more than sex objects or Oedipal figures. When the sexism is a product of societal values, I can mull it over and let it pass, but when the treatment of women is not merely unintentionally sexist but truly misogynistic, I let my inner feminist loose. Anger obscures my objective judgment, and I slam my book shut, dust clouds billowing from the pages.

While I have managed to find some equilibrium, I sometimes get so fed up that I want to renounce my feminism, as though I were getting rid of a membership to a club, and be able to go to the movies without feeling like I have to topple the patriarchy. However, I know that I never will and never could; I’m far too proud of being a feminist, and I mostly do find the dialogue it creates to be wonderful and stimulating. I just hope that, one day, when women write (and publish) half of the world’s fiction, all the tropes of damsels in distress and manic, pixie dream girls will have faded away. But until then, enjoying a good piece of 19th or 20th century literature for its artistic merits shouldn’t be stressful; it should be thought-provoking, and perhaps even fun.

When you feel guilty for liking sexist storytelling, give yourself a pat on the back for even bothering to notice what often flits past people’s gazes. I believe it’s good to recognize flaws in the things you love, much in the way you accept that your best friend may do things that occasionally irk you. Sometimes you have to think it over and shrug it off, because you can’t change what has already been written. The ink has dried by now, and all you can do is choose how to react to the words on the page.