Since when do media models define who we are, whatever their color?

Column by Sarah ’11

I don’t know what to say about the trend of racial ambiguous models in the media. Not that I don’t have an opinion on what makes a person beautiful. There are the universally flattering traits that make everyone look like rock stars – the genuine laugh, the courage to be one’s own self – but I feel that as young women attending an uber-feminist institution like Marlborough, we get reminded of the importance of the cultivation of these traits on a daily basis, and we are perhaps even beaten-over-the-head with these reminders. So I will refrain from beating you over the head any further.

Honestly, I never really analyze aesthetic on a level deeper than, “I love the draping on your top!” or “The colors in that painting are really bright. They make me feel happy.” If you showed me Michelangelo’s “The David,” I’m not really going to perceive much more than a very large, very naked man. My beauty standards are pretty – well – standard.

So I think that the models in magazines look great, and I’m not offended by their beanpole physiques that manage to make clothes look pretty! And I don’t have too many ideas on how to revolutionize the beauty industry, or how to manage to ethnically label models without coming across as superficial, or the best way to make everyone feel beautiful and warm and fuzzy inside! So sue me.

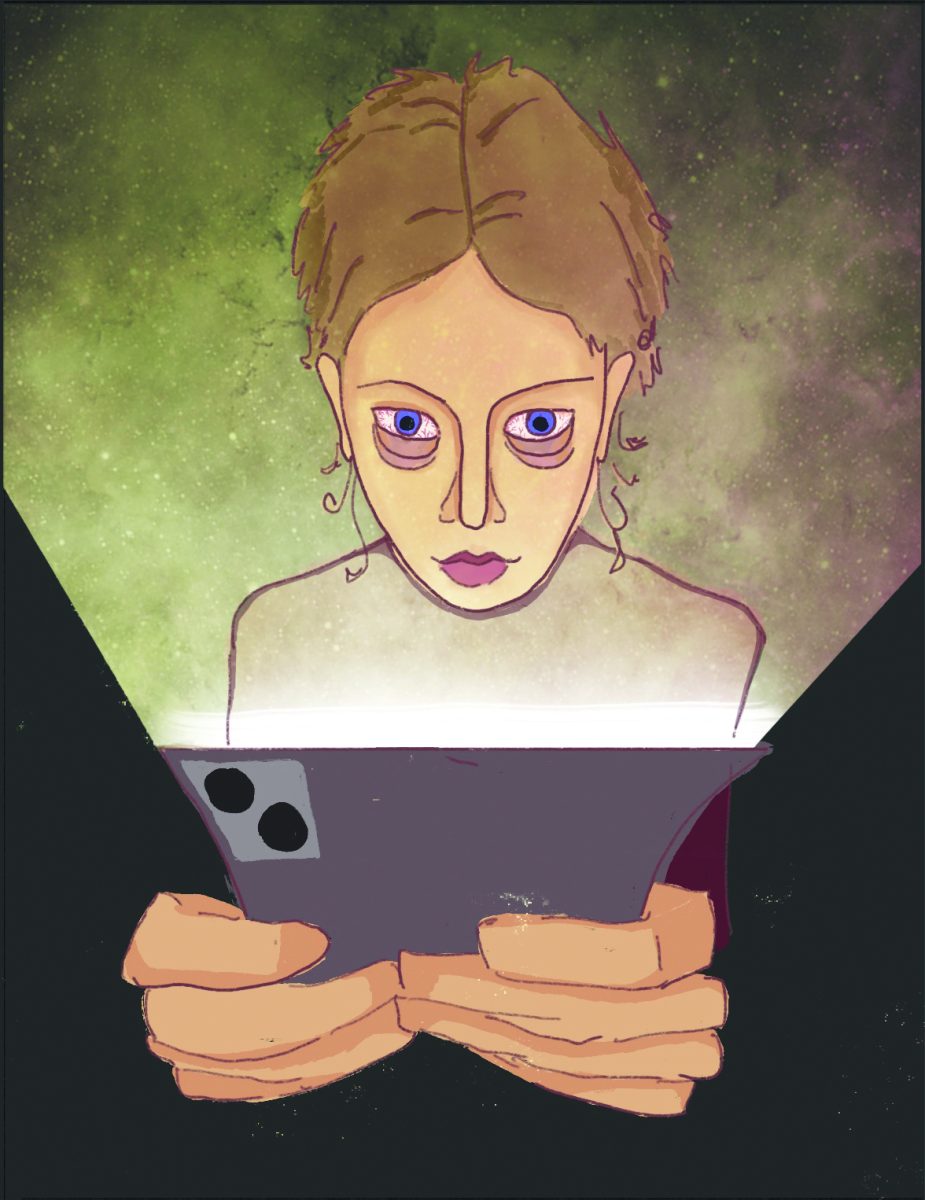

If people are feeling ugly because of the skin color or body type that the media portrays as “beauty,” there’s nothing that society is going to do about it right now. The real problem that people are having is not with the power of the media but with the strength of their own self-reliance. They should stop fine-tuning the frequencies with which they can hear society’s labels and try honing their own holistic definitions of themselves with regards to their individual identities.

And that is why I laugh when people try to guess at my race. As a biracial person, I know that the labels society can plaster onto my college applications can be accurate to some extent. They might even give you some insight into my actions in relationship to my cultural heritage. (Case in point: women in my family freely tell each other when it looks like they’ve gained weight, because in China, calling someone fat is not that big of a deal.) But I know that no matter how hard we try to portray these labels as actually being the reasons behind our physiques or self-image, or actually use them as excuses for our behavior, we fundamentally miss the point of who we are. A label can only define a person so far, because the rest is up to us.

So call me Chinese. Call me Asian American. Call me Caucasian, Jewish, Hungarian-Jewish, whatever. Maybe even call me a vague term like multiethnic. After all, as every junior in AP English Lit knows, ambiguity is richness.