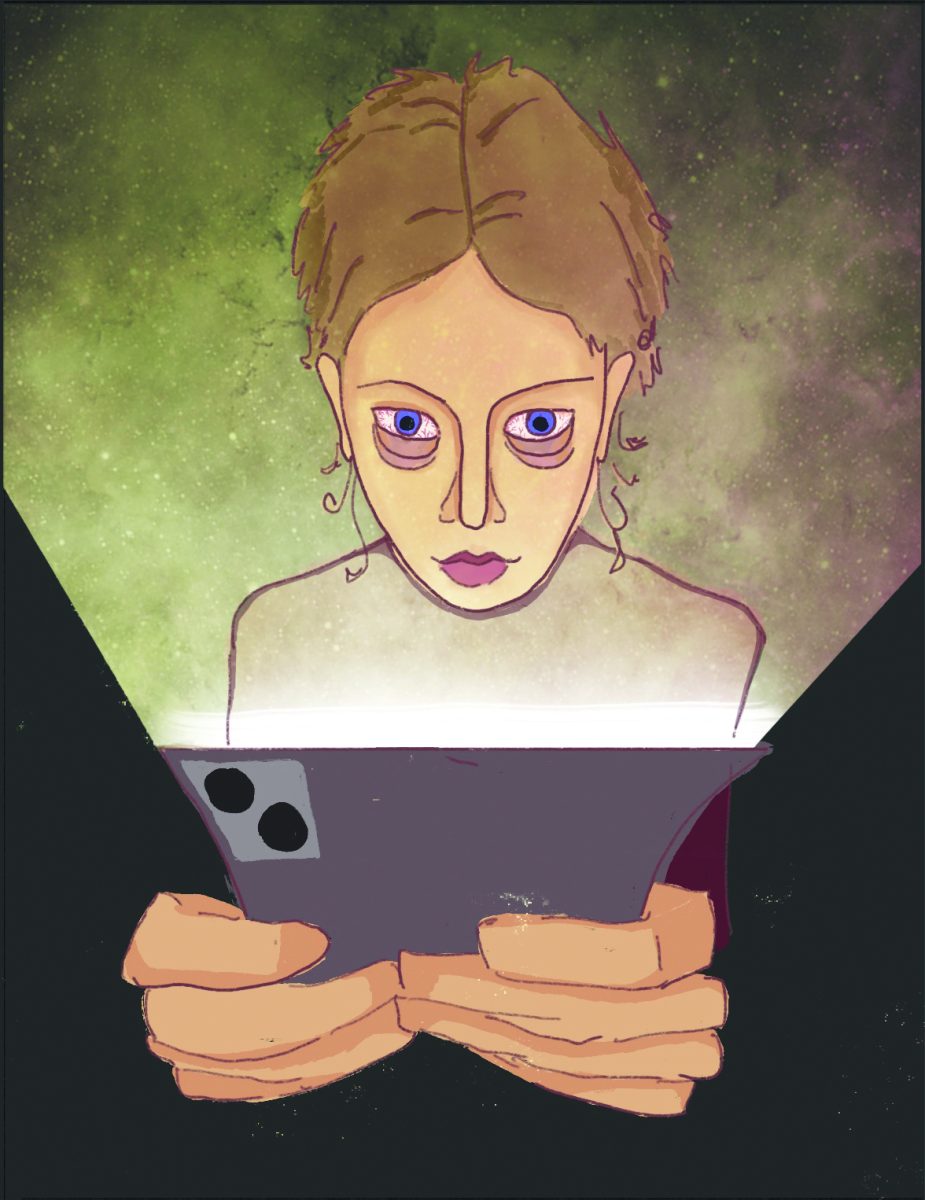

In the past few years, Marlborough School has taken a new and admirable approach to diversity. As a community, we have tried to implement better ways to talk about issues such as race, sexuality and socio-economic differences. However, what the School has not effectively addressed are many of the ingrained social habits that students practice on a daily basis.

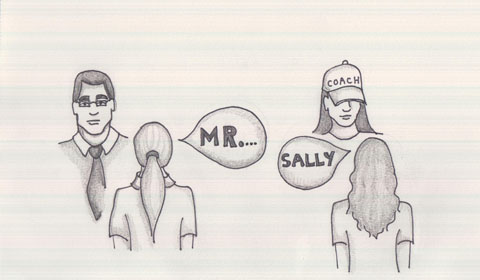

Students at Marlborough use last names and titles—Dr., Mr., Mrs, etc.—to refer to their teachers and advisors, but we often refer to our coaches and to the School’s maintenance and security personnel by their first names.

What does this say about us as a community? Are we perpetuating old societal norms? Should we continue using this standard, or should we break from it?

Most people on campus, whether they are students, teachers or administrators, would agree that it is proper to address a respected community member by his or her title. We reserve special titles, for example, to refer to judges, medical doctors, leaders in the armed forces, and people who have PhDs.

We are introduced to our teachers on the first day of school as Ms., Mrs., Mr. or Dr. Even staff members like physical education instructor Naoto Tashiro, who used to be a coach, is now referred to by students as Coach Tashiro or Mr. Tashiro.

We do not know why teachers introduce themselves in such a way. Faculty members and administrators may feel pressure to be called by their titles and last names in order to adhere to society’s expectations. Another possibility is that teachers feel as though they need titles and formality in order to maintain respect and control in the classroom.

When we call someone by his or her first name, it is often because we feel as though we are in some form an equal to him or her, thereby creating a more casual relationship. This may be a reason that coaches and other staff members introduce themselves to students by their first names; they like the informality of being someone who works with students.

But, by reserving titles like Mrs. and Mr. for teachers and administrators, we create an unintentional divide between the adults on campus.

This naming system could be a manifestation of socio-economic issues, which have not been addressed on campus as much as other forms of diversity. Calling teachers with doctoral degrees “Dr.”, for example, may remind us of an era in which only the individuals who had money to pay for years of higher education were lucky enough to get PhDs. Postgraduate study is perhaps more accessible than ever, but the naming norms could be a societal residue from a bygone era.

There is no right answer or single solution that we can point to in order to answer all of the questions that these norms raise. The best way to begin to unearth the truth is to start dialogue about why we use the titles we do, which will hopefully enable us to discover answers and begin to assess what they mean.

We are often unaware of our own social issues and try to focus on issues outside of School, but the journey to a more socially educated and diversity-conscious community starts with addressing the very issues in our community.