What is a clique?

The word “clique” is defined by Merriam-Webster as “a narrow exclusive circle or group of persons,” and especially one that is “held together by common interests, views, or purposes.” Cliques frequently define social hierarchies, particularly for girls, and they can often be toxic or exclusionary.

Social organization is deeply embedded in human behavior and psychology, as cooperation and collaboration have ensured human survival for millennia. At a fundamental level, humans’ social tendencies exist neurologically for safety but have evolved to enable complex social interactions and organizations between humans. The organizations comprise social categorizations such as “friend groups” and “cliques.”

Friendships are often formed due to a common interest or shared activity, such as playing in the same band or going to school together. These friendships can form into friend groups, which can gradually form into hyper-exclusive “cliques” that may perpetuate bullying and categorization within communities. Cliques often form in high schools, and they are frequently seen as an inevitable part of “coming of age” culture.

Popular movies and media about high school life often feature negative depictions of cliques. Perhaps the most famous movie clique is the “Plastics” from the 2004 movie “Mean Girls.” The Plastics are a trio of the most popular girls in school, and the movie follows their exclusionary actions and bullying as a new girl becomes acquainted with the school hierarchy.

The Plastics, along with many other media cliques such as the “Pink Ladies” from “Grease” and the “Heathers” from “Heathers,” are a caricatured portrayal of the meanness present at the top of high school social hierarchies across the U.S. These groups rule the school, but there are also other cliques and “lower” social categorizations that are stereotyped in the media and in high school life.

A Google search of the “rankings of high school friend groups” reveals a tiered list of the typical high school cliques. The top tier includes the “populars,” “jocks” and “cheerleaders,” the middle tier includes “nerds” and “normals” and the bottom tier consists of “loners” or “stoners.” The strict categorization of these groups represents the prevalence of high school social hierarchies and the rigidity that cliques can cause in school communities. In the opening scene of “Mean Girls,” the kinds of cliques that sit at each lunch table are being described to the new girl, revealing how cliques can be binding and perpetuate stereotypes, and they hold students back from interacting with people outside of their social circles.

However, cliques do not always exist in high school environments, and it takes certain social conditions to foster a rigid social hierarchy. A study done by Stanford University examined the existence of cliques in a variety of schools. It concluded that cliques are more likely to be formed in larger and less strict school environments than in small ones because more open school environments trigger a more intense search to find friends with common interests, which facilitates close and sometimes cliquey friendships. On the other hand, due to the confined space of smaller schools, cliques and exclusion are less likely to occur because the cost of excluding someone is higher than in a larger environment. Professor at Stanford Graduate School of Education Daniel McFarland comments on the uncertainty of how to maximize happiness and reduce exclusion.

“The truth is that we are not sure which kind of adolescent society is best for youth social development, let alone what position in them is best,” McFarland said.

McFarland’s study demonstrates how cliques and groupings are shaped by social tendencies, but also by one’s environment. Therefore, cliques can impact high school social lives in various ways, and they can even interfere with other aspects of a student’s life. The social hierarchy within high school life can affect self-confidence, happiness and academic performance.

Impact of cliques

Tight social circles can help teens navigate life inside and outside of school, as these bonds act as forms of support for all members.

Often, finding the right group of friends can be daunting, and many who struggle with this initial interaction start to seek a sense of belonging. This feeling can be so overwhelming that conforming to the likes and dislikes of particular groups may feel like the only way to fit in. This thought may go both ways. Those on the “outside” may adjust their behavior to feel like they belong, and those on the “inside” may search for a specific behavior in those who want to join them. These outlooks are what can lead to harm, both emotionally and mentally.

The act of ostracism in friend groups highlights the darker side of cliques. They can change from being spaces of friendship to modes of exclusion.

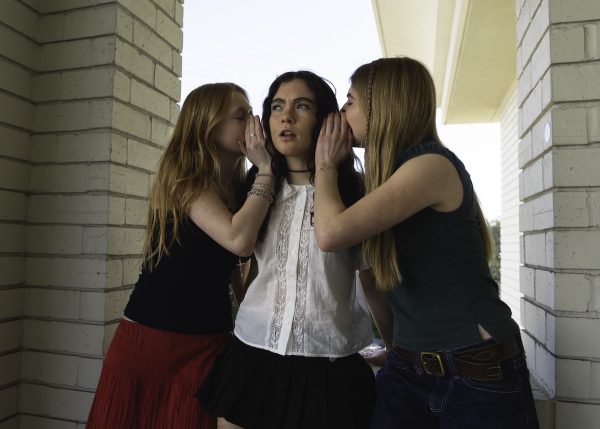

So-called “mean girls” are often characterized as girls who thrive on the idea of exclusivity in the inner circle and keeping unwanted members out. To many, being allowed into an exclusive clique is seen as a privilege and a blessing. But mean girls often gossip, ostracize others, tease, stereotype and even sabotage one another, leading to relational aggression against others and each other.

According to the National Association of School Psychologists, “relational aggression” is defined as “harm within relationships that is caused by covert bullying or manipulative behavior.” This term is deeply rooted in the chemistry and structure of the mean girl stereotype, and it can easily lead to bullying. The implied social power imbalance can cause these girls to perceive others as inferior or lesser than others, leaving them feeling entitled to pick on those who are outside their inner circle.

In attempts to insert oneself into this supposedly “popular” and “honorable” inner circle, people can unconsciously push others down. Sometimes they will ignore the people they truly value and share interests with to be accepted into a friend group that has higher perceived social legitimacy within their school.

In many ways, this popularity contest aligns with the culture of social media. With public statistics centering the amount of likes, followers, posts, comments and shares a user receives, the need to feel liked and accepted by others increases in all areas of life.

“Social media can make some adolescents feel more included. Especially if, for example, you aren’t feeling connected to your friend group at school, you might have found those connections through social media,” Director of Education and Counseling Services Morgan Duggan said.

Social platforms can easily reinforce relationships, making connecting with people in and out of school easier.

“On the flip side of being on social media and seeing other people hanging out, it could create an even bigger feeling of exclusion,” School Psychologist Cristina Lopez-Green said.

Although social media is a way for adolescents to connect, there is a risk of feeling left out as well. According to a study published by the National Library of Medicine, a higher percentage of girls were seen on social media, and when comparing their mental health to that of their male counterparts, they had reportedly lower amounts of emotions corresponding with well-being. Charlie ’25 commented on the way that social media has falsely portrayed groups of people as cliquey or exclusive.

“Social media makes people seem more intimidating and exclusive than they actually are in real life, and it makes people less encouraged to make new friends,” Charlie said. “It also makes friend groups seem more exclusive than they actually are.”

On the other hand, social media can also be used to create and sustain friendships and that would otherwise not be maintained. A Pew Research Center Study found that two-thirds of teenagers have shared their social media usernames with new acquaintances to stay in touch, two-thirds of teenagers named social media as one of their top methods of communication with their friends and 70% of teens feel that social media allows them to connect with their friends’ feelings. Similarly, many Marlborough students cited social media as a way for them to connect with new people.

“Social media has made it easier for me to make friends outside of my group because I can easily see people’s interests and if they align with mine,” Avery ’27, who is also a UV staffer, said.

At Marlborough

In the past several decades, technology has advanced rapidly, creating more avenues for communication and connection. Young adolescents are often exposed to various forms of this technology, mainly in the forms of social media, which can have a large impact on their development and socialization as they reach adulthood.

Platforms like Instagram, TikTok and Snapchat are especially prevalent in middle and high schoolers’ lives, allowing them to share more aspects of their lives with a larger audience of peers.

In many ways, students see social media as an easy and accessible way to stay in touch with friends outside of school, connect to other students with similar interests and entertain themselves.

“On social media, you are connected with people you have similarities with,” Charley ’30 said. “You meet people with common interests, and that might make finding friends easier.”

Initiating connections between those who share similar interests can lead to the exclusion of those who do not “fit” into those categories. Social media can also cause students to become less social in person and resort to their phones and devices for interaction with others instead.

“I am not allowed to get social media, and I get excluded often because I don’t have Snapchat and that’s where most of my friends make plans and text,” one student said.

In a survey sent out to Marlborough students, respondents were asked to evaluate exclusionary behavior inside and outside of their friend groups at Marlborough. When asked if they have a “defined” friend group, 79.4% of the survey’s 63 respondents said yes, while the other 20.6% responded maybe or no. This data suggests that Marlborough is generally categorized by friend groups. The survey defines a friend group as a group that sits together at lunch, has a set group of people or has a title.

Many Marlborough students also expressed that they feel that it is easy to connect to peers outside of their friend groups. In the same survey, 58.7% of respondents said that it is easy to make friends outside of their usual friend group, and 31.7% of respondents said that it is somewhat easy.

This connection outside of friend groups fluctuates as students transition from middle to high school. Clara ’26 said she thinks that it is much easier to connect with a larger group of friends in high school than in middle school.

“It is definitely easier to make friends in high school than middle school,” Clara said. “People are much more willing to branch out and connect with a broader variety of people the older and more comfortable at Marlborough they get.”

Additionally, a student said she noticed increased intermingling between friend groups when high school began.

“Starting in junior year, I noticed that what used to seem like very clear friend groups started to look more like a blur of everybody hanging out with each other,” the student said.

However, the friend group culture within Marlborough may only be reflective of the structure within an all-girls school environment, rather than a co-ed school. Savannah ’25, a student at the large co-ed school Harvard Westlake in Los Angeles, commented on the nature of friend groups in her school environment.

“Because of how big Harvard Westlake is, you get the best of both worlds because you know everyone and hang out with pretty much everyone, but you can still have a really tight friend group,” Savannah said.

Ria ’26 echoed this sentiment about the smaller all-girls Marlborough community, describing that she finds friendship and community both in and out of her friend group.

“Even though Marlborough is a pretty small community, I have found both an amazing friend group and amazing friendships outside of that group,” Ria said. “I am surrounded by the most incredible support system and group of friends, which I think is a true testament to the sisterhood and community within Marlborough.”