Since the 2020 election, the voter landscape has been gradually changing. According to The New York Times, voters of color have increasingly shifted to the Republican Party, a reversal of the voting trends that have existed since the 1960s.

The Civil Rights era marked the first racial realignment in politics. As white voters moved to the political right, people of color (POC) began to support the Democratic Party for its developing “anti-racist” ideals and its identity-based political approach, in which a party tries to gain the support of a specific minority population through rhetoric or policies speaking to general aspects of the group’s identity. The party’s support of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, among other legislation, only strengthened its support from POC. Over the next few decades, POC became a reliably Democratic demographic. Yet, as our most recent election has indicated and some scholars have argued, POC may no longer be a dependable voter base for the Democratic Party.

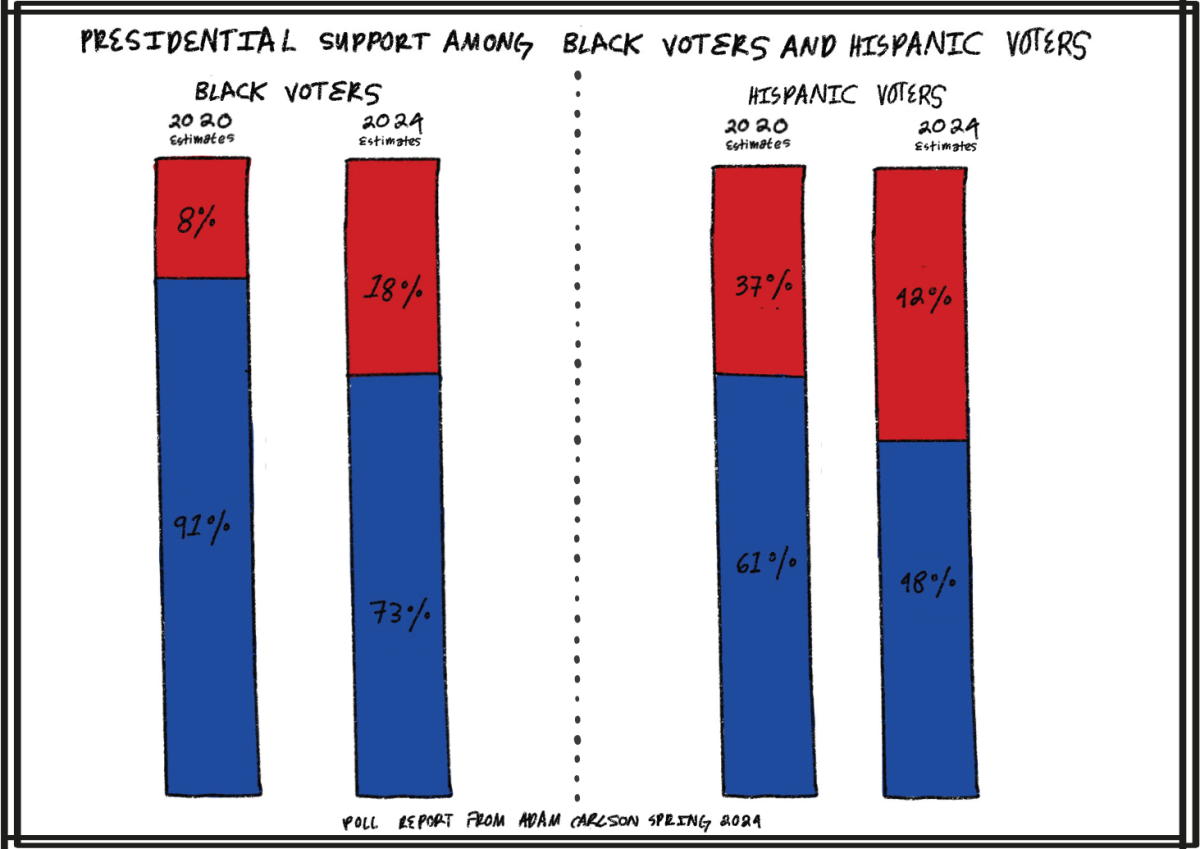

While the majority of POC continue to vote left, that majority is decreasing each year. In the spring of 2024, pollster Adam Carlson combined data from 10 polling firms to report that President Joe Biden led Donald Trump by 55 percentage points among Black voters, much less than his 83-point margin in 2020. Biden led by six points among Latino voters, compared to his 24-point lead in 2020.

Scholars such as Jay Caspian Kang and Eduardo Bonilla-Silva have identified multiple causes for this shift. One main cause is that the anti-racist messaging of the Democratic party no longer resonates with some within communities of color. Rather, the right-wing messaging that highlights the values of capitalism, hard work and freedom is proving more attractive to POC groups throughout the U.S., particularly to immigrant communities.

In fact, when immigrants come to the U.S., the majority of them do not consider themselves to be American or a part of a racial minority coalition that the Democratic party has tried to develop. According to the Pew Research Center, only 14% of Asian immigrants consider themselves to be American, and only 19% of Asian immigrants identify with the label Asian American. Immigrants are more concerned with making a livelihood than they are with being a part of a multiracial alliance that has the goal of defeating race-based persecution in America.

Another reason for the shift in voting trends is that many first-generation immigrants who do not speak English rely on culture-specific social media apps to access American culture. According to The New York Times, apps like WeChat for the Chinese-American community have become the main window through which non-English-speaking immigrants see and understand American politics, and right-wing messaging is prevalent on these apps.

“Conservative messaging seeps into non-English social media,” Head of the History Department Mabel Wong said. “For example, within the AAPI community, Southeast Asian Americans have shifted right, particularly Vietnamese Americans, for a whole host of reasons. One interesting reason is the ways in which Vietnamese social media in America is very much dominated by conservative messaging. The left hasn’t utilized or tapped into that.”

The implications of this shift in voting trends are vast. Immigrant communities are critical to any political campaign. Many crucial swing states have large numbers of eligible immigrant voters. According to The New York Times, for example, approximately 23% of eligible voters in both Arizona and Nevada are Latino. Trump’s victory over all seven swing states in the 2024 election suggests some people of color did shift to vote for the Republican Party. We are waiting on finalized election statistics to support this claim.

As a result, Wong said that the left may have to reconsider its identity-based political strategy if it wants to regain a stronger hold of one of its most important voter bases: people of color.

“This [pattern] opens up an opportunity for the left to rethink its messaging and for us to have a much more nuanced discussion about race,” Wong said. “The conventional ways in which we talk about race and racism no longer apply because the racial landscape in this country is so different now than it was in the ’60s, ’70s, ’80s and even the 90s.”