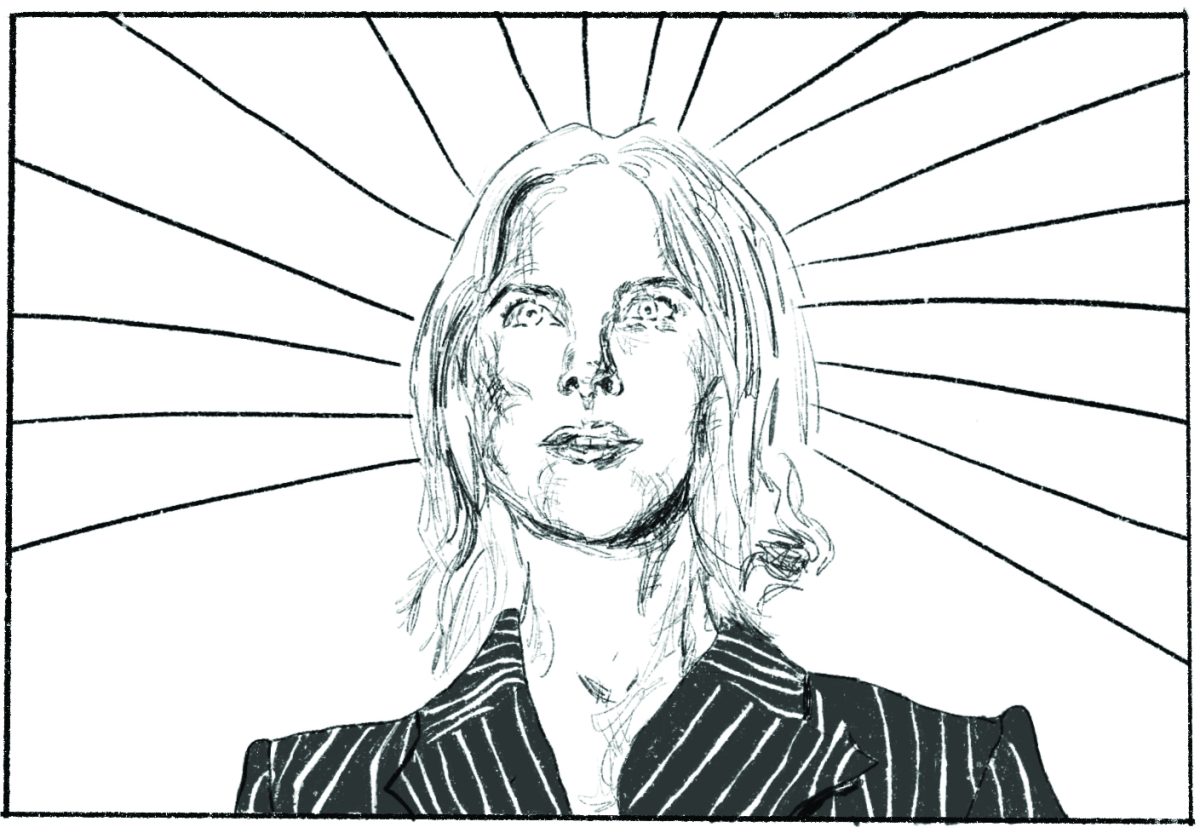

I want you to take a moment to close your eyes and whisper these words: “Heartbreak feels good in a place like this.” Immediately, you are transported to an AMC theater, waiting for your movie to start and finding yourself immersed in the AMC Cineplex in Porter Ranch where the iconic Nicole Kidman advertisement (dare I say short film?) was created. You see Kidman gliding gracefully to the theater where she is “not just entertained, but somehow reborn,” watching films like “La La Land,” “Wonder Woman” and more. Your theater erupts in applause with the same gusto as the audience at Sundance’s hottest new movie.

How can a woman’s delivery of a 60-second monologue in a sparkling pantsuit be so profoundly effective in becoming an instant classic and a household meme? The beauty lies in how the simplicity of the commercial intertwines with a clear lack of irony in the piece’s tone. This stubborn sincerity is what makes the piece the marvel of camp that it’s become.

Camp is what elevates the commercial from a reminder to silence your cellphone into a cult classic advertisement campaign. Late American culture critic Susan Sontag, in her essay “Notes on Camp,” identifies the aesthetic as the “sensibility of failed seriousness, of the theatricalization of experience” and the “glorification of ‘character.’” Sontag states that “the pure examples of Camp are unintentional; they are dead serious.”

The Nicole Kidman ad falls into this category of unintentional camp because it is serious enough in tone to convince me that it was intended to land earnestly, rather than comedically. The emphasis on emotion — laughing, crying, caring “that indescribable feeling” — is meant to pull at heartstrings and reminds movie-watching homebodies of the connection that they can only find in theaters.

I think the “theatricalization of experience” resonates in Kidman’s performance. Not only is she the only one inside of the theater, but every move she makes is drawn out and dramatic — she walks languidly down the hall,

strolls through the aisle and drapes herself in her seat. She draws a connection between her and her viewers by only using “we” pronouns and emphasizes how, at the movies, we are “reborn … together.” While alone, she amplifies the camaraderie of a theater

crowd, making the experience much more dramatic. In doing so, she demonstrates the “glorification of ‘character’” that Sontag mentions. “Character” is in quotes to emphasize the exaggeration that camp requires: In this piece, Nicole Kidman plays herself; however, this version of herself is exaggerated to fill a cartoonish movie star role. She’s not just the main character, she’s the “main character.” All of these aspects contribute first to the campiness of the piece, and to the audience’s adoring response.

Viewers have such a big reaction to the ad because truly nothing like it has been done before. There’s a seriousness, blind to its own irony, that is somehow endearing and is met with love rather than ridicule — something uncommon for large-scale commer-cials like this one. The piece is confident and emphatically emotional, even with its unintentionally campy nature. It’s a one-of-a-kind paradox of dead serious camp, and I, personally, will always give a hearty cheer for Kidman’s award-worthy performance. When all is said and done, I must admit: AMC theaters … they make movies better.