A polo-clad girl filed past the screen in the back of Caswell Hall. The projector emitted a blurred freeze frame depicting the wide-eyed face of a ten year old child and, behind him, a black AK-47.

Madeleine, a former child soldier from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) who served in the army from ages 11-14, spoke to juniors and seniors about her three years of service in the army, where she was repeatedly raped and forced to perform acts of violence. About 200 students attended the April 29 event, though it was only required for students in the Regional Studies history elective.

Madeleine said that female child soldiers are especially victimized.

“Not only were we soldiers, but we were there as sexual slaves,” she said. “Many of us girls came home with babies, and not only with babies, but with HIV-AIDS.”

Yet Madeleine dwelled on the darker details of her story only briefly and spent more time describing her rehabilitation and her decision to testify against the generals at the United Nations and the International Criminal Court. She also challenged students to use their own voices for good.

“You have a chance to be raised in a powerful country. You in this country, you can be heard,” Madeleine said, “which is different from my country.”

Bukeni Waruzi, director of a Congolese NGO called Ajedi-Ka, also spoke on the issue of child soldiers. His group goes into military camps in the DRC to negotiate with commanders to free children. So far, he said, the group has freed more than 300 child soldiers from the squalid camp conditions, where many contract diseases or suffer from hunger.

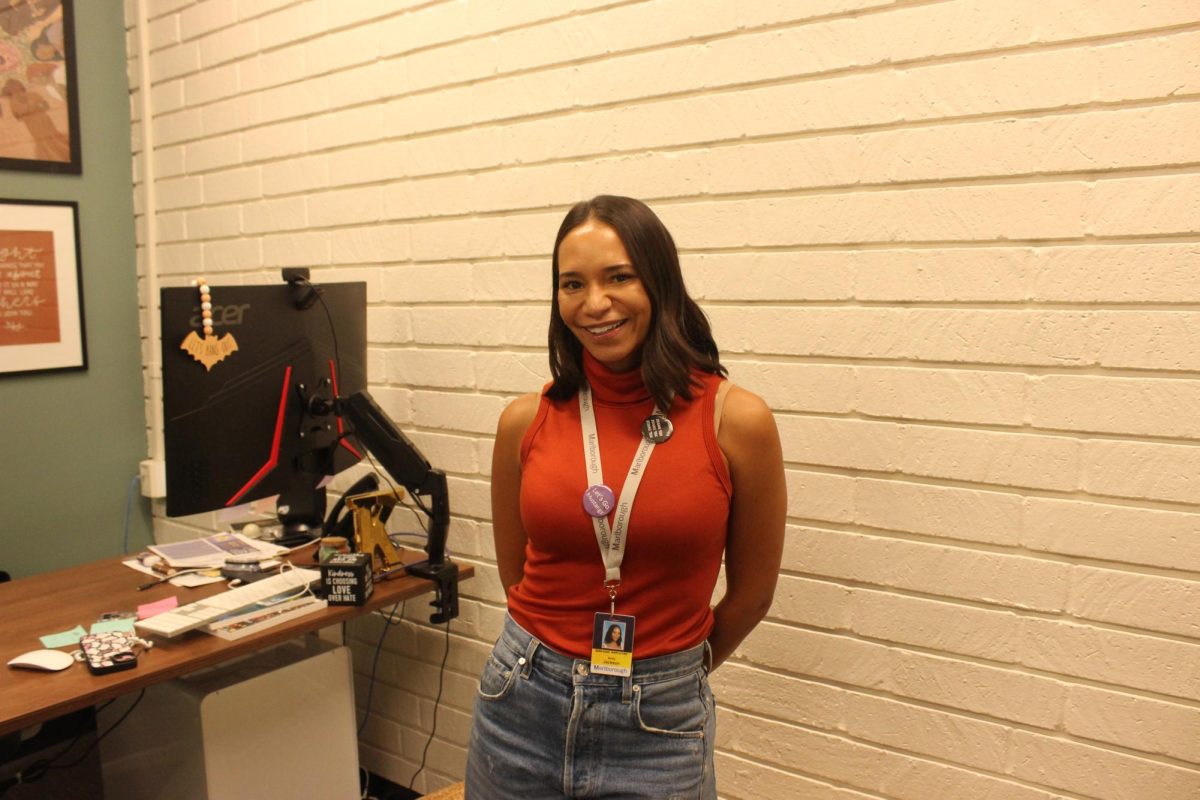

Nancy Nazarian Medina, program director of the Human Rights Watch student task force, gave the opening speech. History and Social Sciences Department Head Catherine Atwell said that Medina is an Honors Research in Humanities mentor for Amy Calfas ’09, and it was Calfas who linked Marlborough with Madeleine and the Human Rights Watch.

Medina thanked Madeleine and Waruzi for sharing their stories. This was the third day of their tour, she said.

“They have been such incredible troopers,” Medina said.

An awkward laugh rippled through the room at her word choice.

Waruzi spoke following Medina’s introduction. He described seeing a nine year old in one of the camps who couldn’t even lift an AK-47.

“I was asking myself, what is she doing here?” he said. “They train her how to kill, how to smoke marijuana, how to cause violence, how to kill her own relatives.”

Waruzi said that students are his favorite audience to speak to about the issue because they have a sensitivity to children that adults sometimes lack. Learning about the issue now, he said, may mean that students are equipped to change things in the future.

Waruzi also showed a documentary “A Duty to Protect,” which depicted female child soldiers telling their stories.

One, a 16 year old named January, sat dressed in a camouflage suit and wore a dark green hat pulled over her forehead. She said she is a sergeant first class and doesn’t want to leave the army because she has worked hard for her rank, and she described some of her duties.

“I like to go to the front lines on drugs. I have no pity when I’m on drugs,” she said. “My strength is killing with knives and rope.”

Another female soldier, 15 year old Mafille, was freed by Waruzi’s organization. Looking at her hands and picking at her fingernails, she described her experience in the camp.

“Before that, I didn’t know men. My first experience was being taken by force,” Mafille said. “I cry whenever I think about it.”

Waruzi said one of the main things American students can do is help contribute to educating Congolese children.

“It is cheap, the education in our country. It only costs about $150, which is the equivalent of maybe two CD’s of Jay-Z,” he said.”

Regional Studies student Tracy ’10 said the speeches were fascinating.

“It seemed so strange that she is a junior, so we’re at the same place, but living completely different lifestyles. It really broadens your perspective,” she said.

Atwell agreed. “It’s always inspiring for me to meet people who have displayed such personal courage,” she said “There’s a certain disconnect when you see it in a film or read it in a book…seeing them in the flesh is so much different.”

At the end of the program, Madeleine took questions. Asked how it was being in school in the United States, she responded with a quiet smile, “It’s OK.”

Medina took the mic.

“She’s being too modest. When Madeleine came to the United States, she didn’t speak any English at all,” Medina said. “This morning, she was up early already working on her homework. She’s preparing for the SAT’s.”