On Dec. 5, violence erupted in Bangui, the capital of the Central African Republic, between the Muslim coalition Seleka, currently in control of the country, and Christian militias attempting to gain territory and wreak revenge following Seleka’s March 2013 coup.

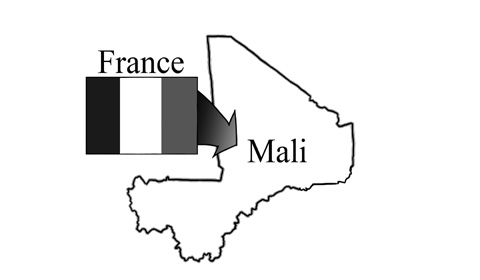

The fighting, which caused an estimated 50 casualties, took place only hours before the proposition of a UN resolution to increase the number of African Union troops in the country from 2,000 to 3,600 in response to the increasing infighting between Christian and Muslim factions. While the resolution to increase the armed presence within the country was approved unanimously the Security Council declined to send in a UN peacekeeping force or to approve the full 6,000 to 9,000 troops recommended by the Secretary General due to the cost of these measures. Instead, the strongest call to arms came from France, who vowed to increase its own presence. France’s deployment of troops in Mali, which was followed by an even faster response to the situation in the Central African Republic, represents a new, much needed willingness in the international community to quash problems before they spiral out of control and to eliminate potential breeding grounds for attacks against the West.

Seleka, an alliance of anti-government militias from the largely Muslim north, accused President Francois Bozizé of violating the terms of a series of peace treaties intended to cement a power-sharing agreement between the Muslim rebels and Bozizé’s supporters, including Central African Christians. The group marched on the capitol in March 2013 and ousted Bozizé, a former military leader who had himself gained power in a 2003 coup. They then installed their leader, Michel Djotodia, as president.

Yet the coalition’s leaders proved unwilling or unable to curb Seleka’s group’s violence. In response, members of the country’s Christian majority formed vigilante groups, striking back at both Seleka forces and members of the city’s Muslim community. The sectarian nature of the violence has led some to label the country “the next Rwanda,” although Djotodia has called such statements trumped-up attempts to manipulate international opinion. On Jan. 10, Djotodia stepped down at a conference of regional leaders called at the request of Chadian President Idriss Deby Itno. Parliamentary leader Alexandre Ferdinand Nguendet was named interim leader until presidential elections can be held. However, it remains to be seen if the controversial president’s resignation will satisfy the anger of a disaffected population, or if the apparent power vacuum will only increase the sectarian violence.

France’s return to Mali and the Central African Republic will no doubt reawaken old tensions between France and its former colonies. Premature, panicked calls of genocide aside, there can be little doubt that if it had been left unattended by the global community, the situation would have only continued to fester. France’s timely intervention ensures that the cycle of retaliation between Christians and Muslims will not continue to escalate. While rapid foreign intervention may be controversial, it can also be life saving.

The U.S. has soured on direct intervention, preferring techniques such as drone strikes and offshore balancing or the use of air strikes in connection with supporting local forces. Yet such methods have dangerous consequences, from the loss of civilian life to the risk of allies’ lack of commitment. Putting troops on the ground can have disastrous consequences should the country that is intervening fail to adequately understand the situation. However, France has demonstrated that, used correctly, military intervention can be an effective tool and should therefore not be removed from the U.S.’s range of options.