Perusing book and film reviews (a hobby of mine), I’ve begun to notice how often authors and filmmakers are commended for their “strong female characters.” As I have established that I am a feminist, this remark should probably raise my spirits about the increased sophistication and diversity of female roles in media, yes? Not quite. In fact, I am repelled by the way critics describe women characters, because it often represents a skewed vision of womanhood and definitions of femininity.

Though I consider “strong” to mean well-developed, a character rich in flaws and idiosyncrasies and humanity, I feel that, lately, writers of fiction are using physical strength to compensate for lazy female character arcs. The term “strong female character” is, first and fore- most, irksome because it insinuates that women aren’t naturally strong, physically or otherwise. The phrase is a disclaimer, clarifying something supposedly out of the norm. In one way, I get it. We use the description to differentiate the character from thousands of years of fictional female misrepresentation, but I don’t hear critics commending books and movies for their “sensitive” or “emotional” male characters, traits that people usually (and wrongfully) do not associate with masculinity. No, there are no “strong male characters”; there are only characters who happen to be male (excuse my bitterness).

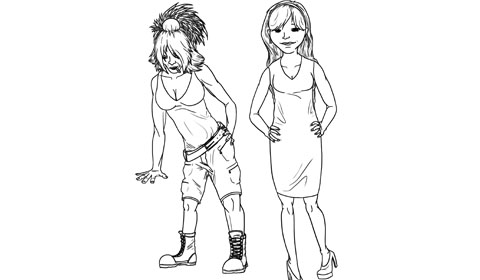

Besides, the description begs the question of what being a “strong” character entails. When I think of how the word is used today, I think back to elementary school, where it some- how became cool for girls to reject femininity and cast off pink to defy the institution. What we deem to be a strong female character is generally a tough woman who wears a permanently dour expression and is “not like other girls.” And that is the thorn in my side, jabbing me right to my feminist core.

I say this once and one time only: It’s okay to be feminine, whatever that means to you. Societally speaking, femininity entails pink, passivity and primness, and if you’re naturally prim and passive, then there’s nothing wrong with that. Or you could be like Scout from To Kill a Mockingbird and prefer to wear overalls and rough-house, which is perfectly all right, too!

Somehow femininity has become a mark of shame, and scorning make- up and dresses for the sake of subversion has become a fashionable act. A female character simply having typically masculine traits doesn’t necessarily strengthen her; it only promotes the view that men are the strong ones in the world, and that to be strong means to emulate them.

It’s irritatingly obvious when a writer purposefully endows a female character with these “strong” traits. This artificiality was one of the reasons I wearied of young adult fiction, which I used to devour. I gradually realized that every character in those books was crafted around the same skeleton, infused with the same traditional toughness. Again, there is nothing wrong with being tough, but simply making a girl tough and rebellious and steeled to the world does not necessarily make her a real character. She needs a past—memories, faults, and burdens—like any other character.

Strengthened character development does not always constitute physical prowess and emotional armor; it means being fleshed-out. When I think of the female characters that have inspired me as a girl, a few that come to mind are Celie in The Color Purple, Addie Loggins in Pa- per Moon, Veronica Sawyer in Heathers—all flawed, all culpable for making mistakes. They are neither strong nor weak in our narrow definitions, but merely characters with their own thoughts and decisions. Writers, take note.