Benjamin Franklin once wrote, “They who would sacrifice essential liberty for temporary security deserve neither liberty, nor security.” Recent revelations about the scope of NSA surveillance have rekindled a centuries-old debate about the balance between safety and privacy in a democracy.

The National Security Agency (NSA) was established in 1952 to gather and analyze data for foreign intelligence. After 9/11, its capabilities rapidly expanded to the domestic sphere, with the addition of three programs: telephone metadata collection, PRISM, XKeyscore.

Metadata, the mass collection of phone records from Verizon Communication Inc., is supposedly justified under Section 215 of the PATRIOT Act. This includes phone location and call duration data—information that can easily be used to find names, addresses and other information about the callers.

PRISM, authorized under Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) Amendment Act (FAA), targets Google, Facebook, or Apple users who live outside the U.S, or people in the U.S. (including citizens) who are communicating with people “reasonably suspected” to be outside the U.S. The NSA gathers search history, email content, file transfers and live chats from these companies. The usefulness of PRISM has recently been called into question with Senators Wyden and Udall (D-CO) claiming that the NSA “significantly exaggerated its effectiveness.”

XKeyscore is a new program that has not yet been authorized by a judicial body. According to a training PowerPoint leaked to The Guardian, the program allows NSA agents to target individuals, even U.S. citizens, based on criteria such as language, encryption, or “suspicious” web searches.

The White House and intelligence officials attempt to justify surveillance by reaffirming judicial and congressional oversight and emphasizing the role of NSA surveillance in stopping terrorist attacks. Closer investigation reveals that neither of these statements is accurate.

“Judicial oversight” is supposedly provided by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC). However, the FISC does not operate in an adversarial manner: Only one side of the argument is heard by the court—the point of view of the intelligence agency asking for approval. As a result, the FISC often panders to NSA requests. Additionally, according to Reggie Walton, the judge who presides over the FISC, the court has no ability to regulate the NSA’s compliance with court decisions.

Congress’s restricted access to information about surveillance activities undermines its role as a check to NSA powers. For example, in March, Director of National Intelligence James Clapper lied under oath to Congress, saying that the NSA was not collecting data on Americans

The public cannot hold the NSA accountable for its actions because all of its actions are shrouded in secrecy. In two lawsuits, Virginia Shubert v. Barack Obama (2006) and Carolyn Jewel v. The National Security Agency (2008) were dismissed because the government claimed “military and state secrets privilege,” meaning they were protected from judicial oversight because it could theoretically compromise national security. This provision allows surveillance to exist outside the realm of public law.

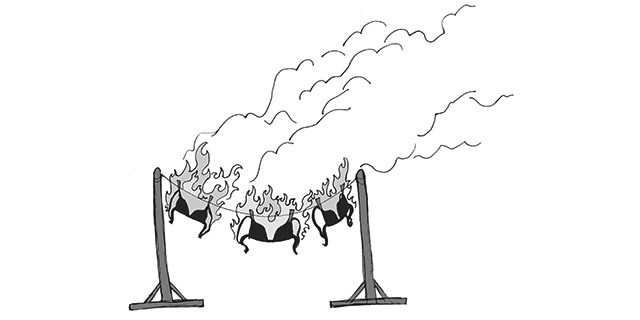

The oft-repeated maxim of the intelligence community is “If you have nothing to hide, you have nothing to fear.” The United States has entered as state of exception in the post-9/11 era; our fear of terrorism undermines the values of constitutional freedoms, and we seem to have adopted a new ideal–that it’s better to be safe than to be free. But why should you be afraid of the NSA’s wide-reaching surveillance powers?

First, surveillance is a threat to free speech. People express themselves differently when they know they are being watched and will be less likely to speak out against government policy if they believe that their opinions will land them on an NSA watch list.

Secondly, abuses of power are already happening within the NSA. According to leaked government records, the frequency of cases in which the NSA stores and potentially searches information it is prohibited from accessing is increasing with little action being taken by the government to curb this trend.

Historically, US intelligence services have used surveillance to target not just suspected criminals, but also activists and public figures (such as Martin Luther King, Jr.) who they perceive as destabilizing domestic forces. As a result, activist groups who criticize the government and try to galvanize public opinion in opposition to federal policies may begin to fear surveillance as a precursor to political persecution and so not be as vocal.

You might think that you have nothing to hide but when it comes down to it, do you know that for sure? We have no idea what the NSA does with the data it collects or what rubrics it uses to classify people as “targets.” This year, as part of the Honors History Seminar course on terrorism, I will be watching Al Qaeda recruitment videos. Does that make me a threat to national security, and a potential target of the NSA? Maybe, maybe not. But if Americans would rather be safe than sorry, shouldn’t we start with being safe from unwarranted scrutiny and targeting from our own government?